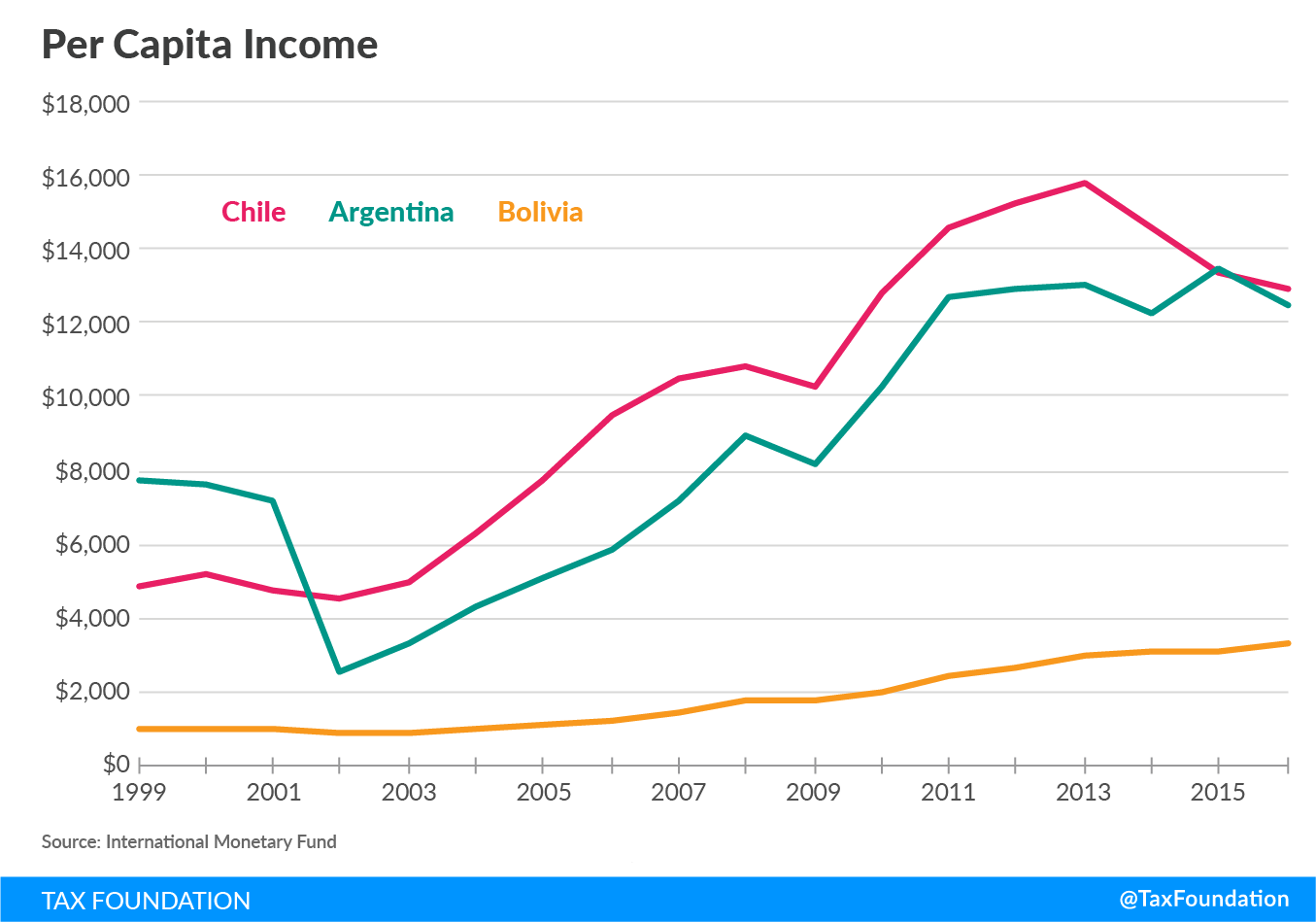

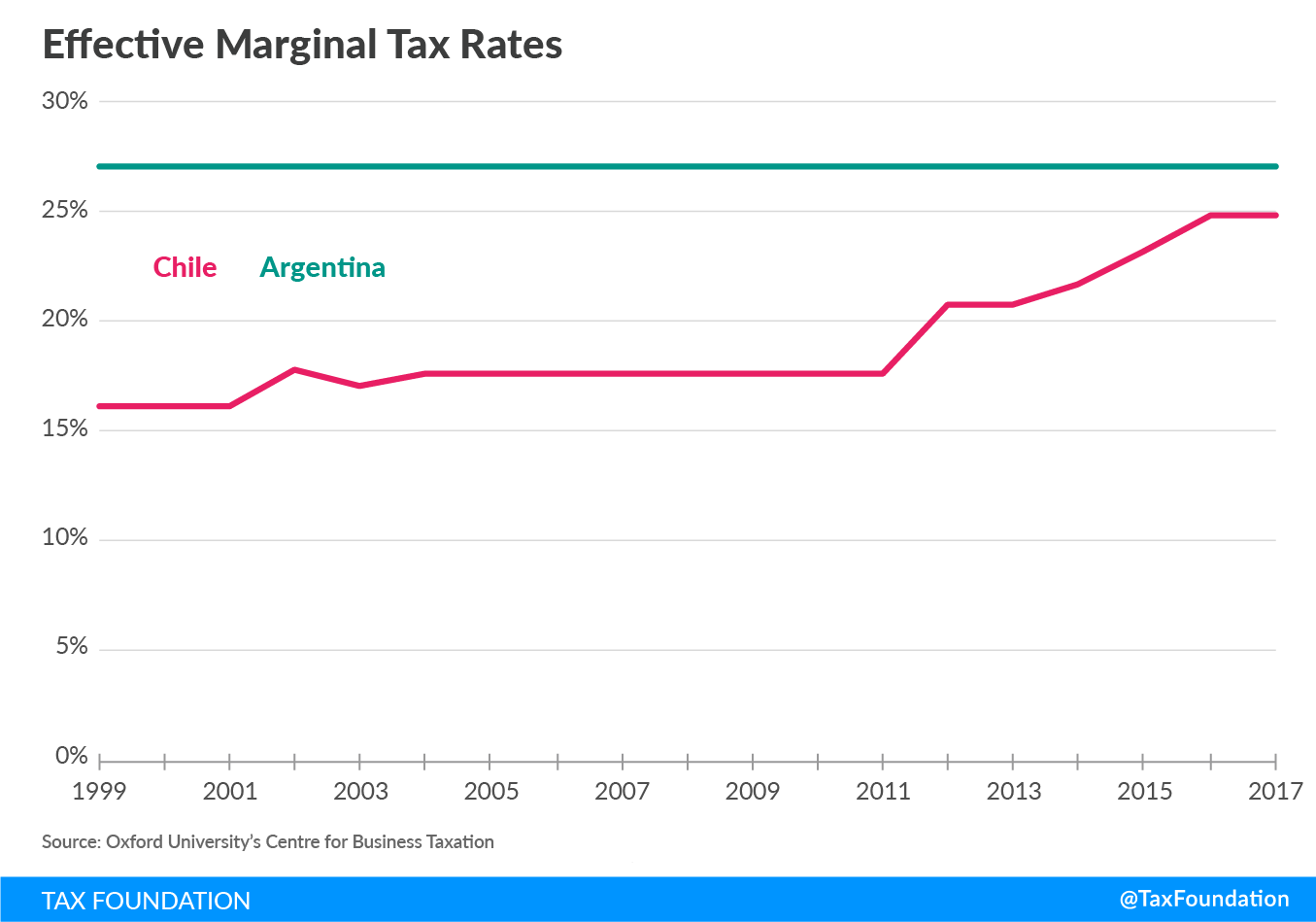

While most countries in the OECD have labored to reduce taxes on businesses, there is one exception. Chile introduced taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform in 2012 and 2014, which increased the corporate tax rates and added stricter anti-tax-avoidance rules. Over the decade before the tax reforms Chile had almost tripled its per capita income of $4,700 in 2001 to almost $14,600 in 2011. Since the tax reform of 2012, the Chilean economy began to slow, and by the 2014 tax reforms, the economy was retracting on a per capita basis. Now, Chile is faced with a recession, even as the global economy is beginning to grow.

Chile was considered the miracle of South America at the end of the 20th century. It emerged from a dictatorial regime under Augusto Pinochet with pro-market reform that opened trade with the rest of the world and brought inflation under control. These reforms, along with a return to democracy, set the stage for a massive economic expansion during the ’90s and drove Chile to become the largest producer of copper in the world. By the beginning of the new century, the per capita income of Chile leaped over its wealthier neighbor, Argentina, and remained $2,000 greater until the tax reform in 2014.

Since the return to democracy in 1989, Chile has averaged around 5 percent growth while its neighbor, Argentina, could barely maintain 2 percent growth. The flood of foreign direct investment (FDI), modern economic institutions, and stable economic growth placed Chile on a path to become a developed nation. Indeed, Chile joined the OECD in 2010, becoming the first nation from South America to sign an accession agreement.

During the presidency of Sebastián Piñera, a center-right politician, mass protests by students forced the Chilean government to reform the education system. As part of the education reforms, Piñera increased the corporate tax rate from 17 percent to 20 percent for 2013 and made the increase retroactive to 2012. These tax changes in the 2012 tax reform bill, along with stricter rules for multinational corporations, raised an additional $1 billion for education even as taxes decreased for individuals.

In the presidential elections of 2013, Michelle Bachelet, a center-left politician, took back the office on a platform of reforming the constitution of Chile and reducing inequality. In September of 2014, she approved a tax reform bill that once again increased the corporate tax rate, to 21 percent in 2014, 22.5 percent in 2015, and 24 percent in 2016. The bill will further increase taxes on shareholders in 2017 and 2018. In addition, the 2014 tax reforms increased anti-tax-avoidance rules and gave the Chilean tax authorities the ability to issue regulations regarding these rules.

President Bachelet promised that the tax reforms would increase tax revenues by 3 percent of GDP by 2018, most of which she would use for social programs. However, in 2015 the Chilean economy began to slow, along with the popularity of Bachelet. By August of 2015, the Chilean central bank cut growth expectations from 3.6 percent to 2.5 percent, which delayed the implementation of Bachelet’s campaign promise of increasing social programs. By the summer of 2016, the sluggish economy weighed on the popularity of Bachelet and brought it to an all-time low.

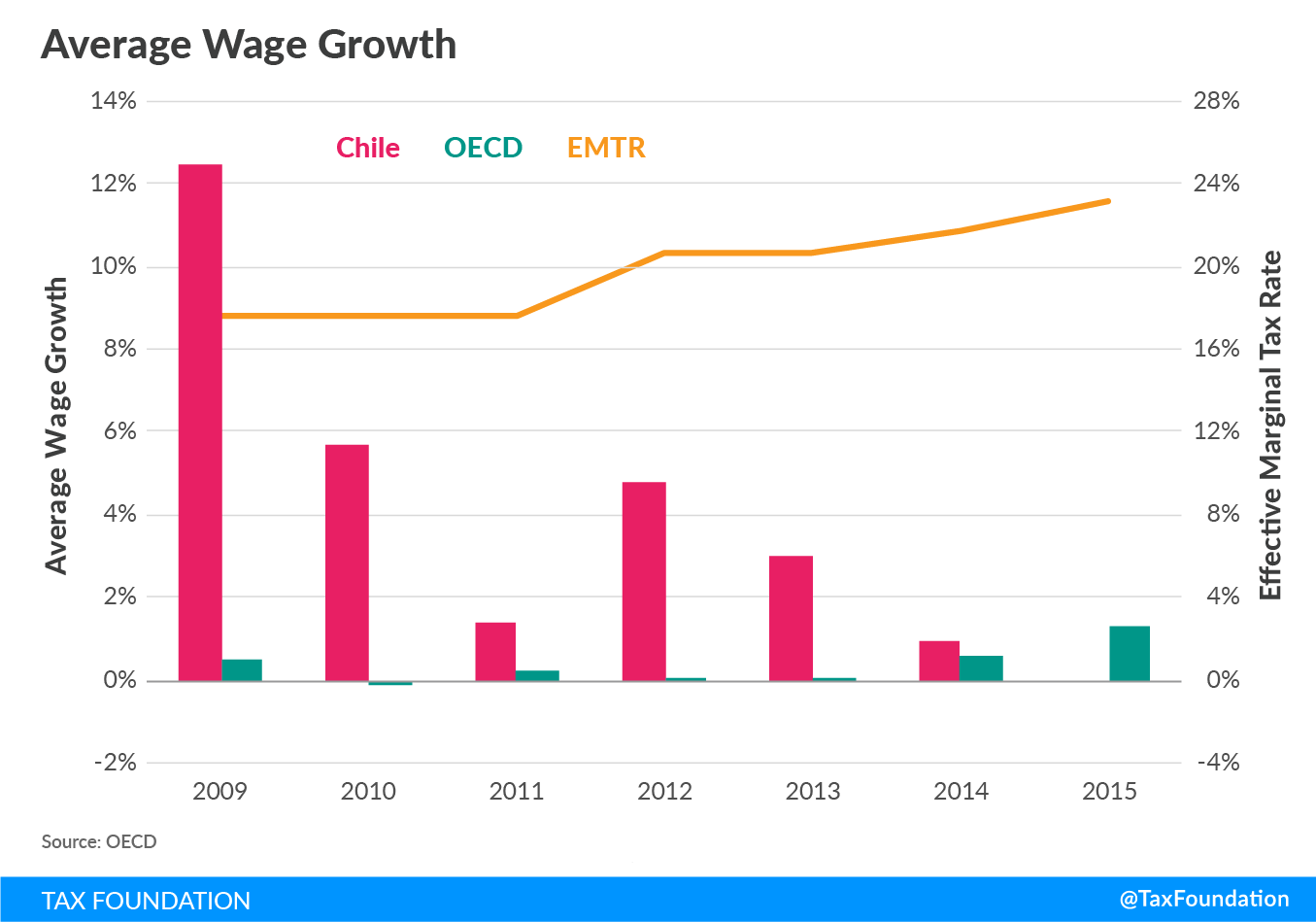

As of the first quarter of 2017, the economic outlook of Chile is rather bleak. The Chilean economy teeters on recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. , with barely 0.1 percent annualized growth in the first quarter. Foreign direct investment has stagnated since its height in 2014 and average wage growth fell to virtually zero in 2015, even as wage growth in the OECD had finally recovered from the Great Recession.

The higher tax burden on mining corporations has squeezed margins and forced companies to delay wage increases. This has sparked conflict with workers’ unions. Standoffs between mining companies and the unions over wages and compensation packages have caused a rash of strikes, which caused a spike in the price of copper at the beginning of this year.

Some have claimed that the strikes are the cause of the declining economic growth, but the reality is the strikes are a symptom of the ailing Chilean economy. The stagnation of FDI and the lower productivity resulting from capital thinning is putting downward pressure on wages. Demanding more compensation as productivity is rising, as happened in the past, is an easy lift for any company. However, when an increased tax burden reduces investment and slows productivity growth, companies are stuck between high taxes on more investment and higher wages to labor, a rock and a hard place.

It is likely the increase in taxes and the uncertainty around the tax rules is the cause of Chile’s current economic woes. Although commodity prices play a role, Chile’s economy is quickly sinking to recession even as the world economy is beginning to grow again. Both President Piñera and President Bachelet had good intentions when raising the taxes on businesses, but these intentions may have paved the way to Chile’s economic ruin.

The current debates over tax reform in the United States have argued that business tax reform is not the country’s most important priority. These tax reform opponents argue that we should be focusing on improving education or reducing inequality. Although these are noble pursuits, using the tax code to achieve them may reduce opportunity for education and wages of the working class due to an ailing economy.

We should take heed from the Chilean experience. Although we are not actively increasing the burden on businesses, we have a tax system out of step with our peers in the OECD. Let’s fix the burden on our economy, and we will find plenty of resources for more education and greater equality in the future.

Share this article