Soda taxes are being sold as a fix for some pretty big problems: everything from obesity to education funding, and everywhere from San Francisco to Philadelphia to West Virginia. Could these sin taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. es really deliver on these promises? Or are proponents glossing over key flaws of these proposals?

Our research has generally concluded that soda taxes are narrow, punitive taxes that are a budget risk not likely to solve America’s health issues. They’re a misguided attempt at solving a multifaceted health problem and will introduce many unintended fiscal consequences.

Soda Taxes Are Regressive

First, let’s remember that these taxes are regressive. My colleague Scott Drenkard wrote in 2012 that a 10 percent soda taxA soda tax is an excise tax on sugary drinks. Most soda taxes apply a flat rate per ounce of a sugar-sweetened beverage. could burden high-income families by $24.29, while poor families would be harmed nearly twice that amount at $47.38.

Proponents sometimes justify this feature of the tax by arguing that it is fine to overtax low-income individuals, as revenue from this tax goes to government services that are enjoyed more by those same low-income individuals. This is poor reasoning, though. If this argument were valid, it could be used to justify any regressive taxA regressive tax is one where the average tax burden decreases with income. Low-income taxpayers pay a disproportionate share of the tax burden, while middle- and high-income taxpayers shoulder a relatively small tax burden. imaginable, as government spending as a whole is progressive, benefiting lower-income individuals more than high-income individuals as a percent of their income.

Using Taxes to Play Caloric Whack-a-mole

While we certainly defer to the judgment of health professionals on the best nutritional choices to make, health experts aren’t unanimous in the belief that soda taxes will make a significant dent in improving health outcomes. A recent study by University of Massachusetts researchers explains the problems with an overly simplistic model of taxation vs. caloric consumption:

Proponents of soda taxes often reference the success of cigarette taxes in decreasing cigarette use. However, cigarettes and soda differ in a number of ways. First, cigarette taxes increase prices significantly, a tactic that may be unjustifiable for soft drinks given that, unlike cigarette use, moderate soda consumption is considered safe. Second, the many available soda substitutes may render soda taxes ineffective, in that consumers will replace highly-taxed beverages with low-tax alternatives with the same health consequences.

If soda becomes too expensive for their liking, consumers may choose to consume another potentially unhealthy drink in its place. According to a 2012 Cornell University study, soda taxes prompted many consumers to switch to beer, while another study suggests that consumers may replace soda with other high-calorie options.

Philadelphia, which recently enacted a soda tax, is starting to find this out. Their 1.5-cents per ounce sugar-sweetened beverage tax doesn’t sound like much, until you realize that the effective tax rate is about 20 times higher than the excise tax for alcohol. Suffice to say, that led to some sticker shock after the tax went into effect. Thanks to Philly’s new tax, at $9.03, a 12-pack of flavored sports drink is more expensive than a 12-pack of beer ($7.99).

This myopic focus with beverages also ignores another aspect of the obesity crisis: food. Most calories come in solid form. Does this mean we should tax every bad calorie someone consumes? Should there be a tax on all-you-can-eat buffets? Maybe a tax on simple carbohydrates of all types, but tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. s for vegetables. It is quickly apparent that the tax code isn’t built to do all of this, nor should it.

A Shrinking, Regressive Tax BaseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. for Education

Besides being depicted as a way to improve public health, soda taxes are also now being looked at as a way to shore up state and local budgets and expand important services such as education. Although it might be more politically expedient to tax a demonized product like soda to pay for popular services, this represents bad fiscal policy. Ideally, public services should be funded by taxes with a broad base and low rate. Soda taxes are the opposite, subjecting a narrow tax base to very high tax rates.

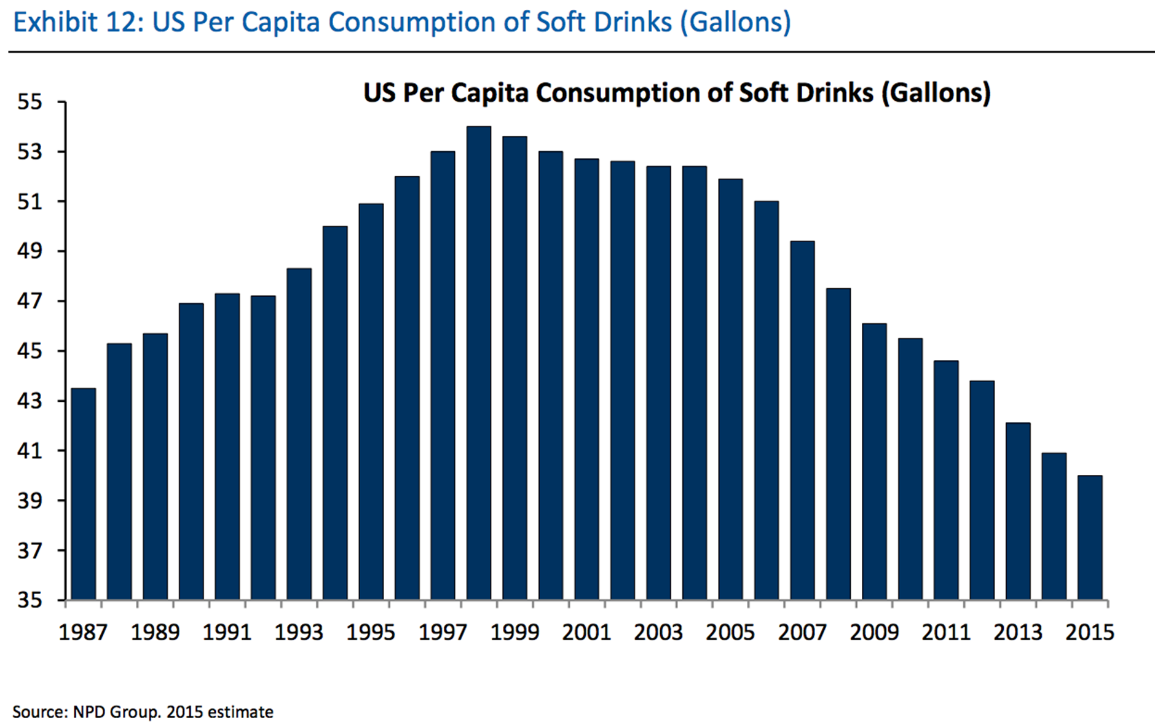

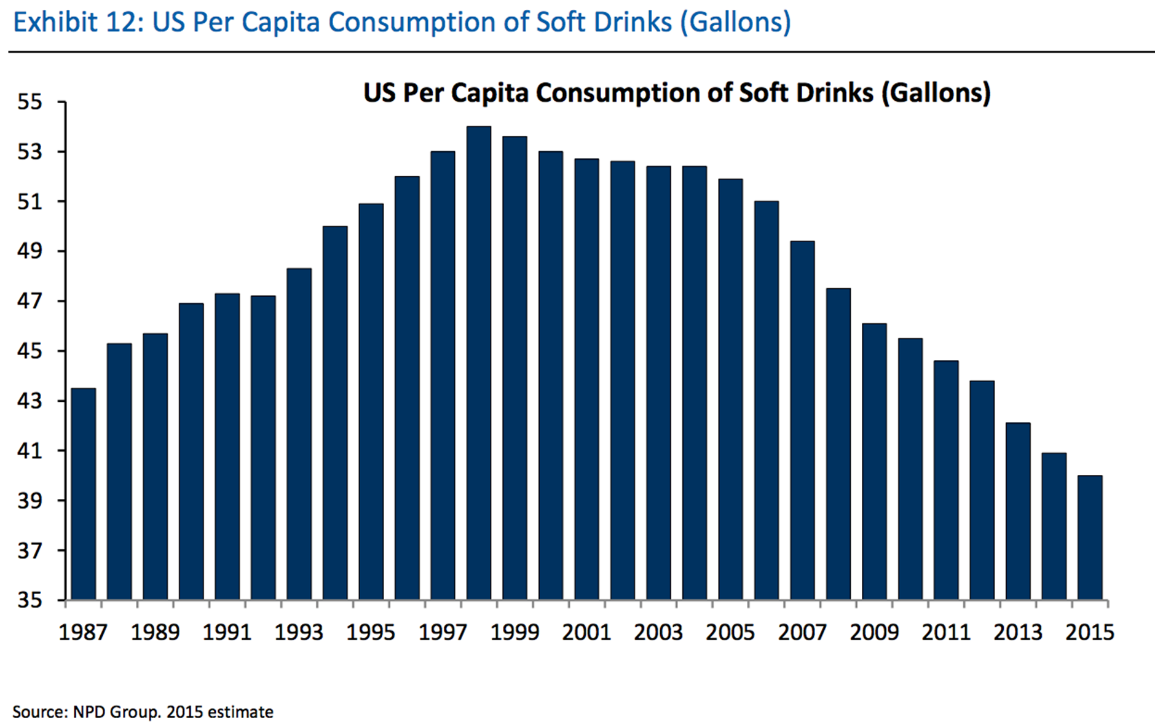

Policymakers should also be aware that soda consumption has already been steadily declining. Enacting a tax on a product with this consumption pattern might result in a temporary spike in revenue, but will soon be followed by a revenue decline as consumers continue shifting their spending habits. Policymakers will face a budget gap from expanding services with a narrowing tax base that doesn’t fill the void.

Economic Consequences

What’s also been lost in the soda tax kerfuffle is the potential job losses, as we’re starting to see in Philadelphia. Retailers, distributors, and restaurants are all bound to be affected, either through smaller profit margins or reduced sales. One beverage company, Pepsi, announced layoffs related to the Philadelphia tax.

At the end of the day, soda taxes are a regressive tax on a product that’s probably fine in moderation. These taxes likely won’t fund what’s being promised, won’t resolve the obesity problem, and will hurt workers and consumers. Based on the mounting evidence, fans of the soda tax might want to take a step back and consider what’s best in the long-term, not just the short-term political gains.

Share