Throughout the 2020 presidential election cycle, many Democratic candidates have suggested raising taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates on corporations and individuals to address income inequality in the United States. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) has proposed returning the corporate rate to 35 percent and imposing a wealth tax in her “Medicare for All” plan. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) is campaigning to impose a progressive wealth tax to target “extreme wealth.”

Across these proposals, however, is a lack of discussion about the economic costs of increasing income tax rates, such as deadweight loss effects. One tenet of sound tax policy is to balance distributional objectives with the distortive effects of high tax rates, which can have disproportionately high economic costs associated with them. Policymakers ought to keep deadweight loss in mind as they consider various proposals.

Deadweight loss (or excess burden) can be defined as the implicit loss associated with imposing a tax that is above the amount of tax paid to the government. This deadweight loss occurs because taxes distort choices and steer resources away from their highest and best use, leaving people worse off than they would be in the absence of the tax.

For example, consider a consumer who buys avocados every week at the grocery store. When avocados cost $2, the consumer purchases five for $10. If the government imposed a tax of 50 cents per avocado, the consumer would face the higher cost of $2.50 per avocado, and we would expect the consumer to reduce the number of avocados purchased. Here the consumer is made worse off by two amounts: the tax revenue transferred to the government and the welfare loss due to reduced consumption.

The relative elasticity (sensitivity to price changes) of producers and consumers in the market determines who bears most of this burden. For example, if consumers are less responsive to price changes relative to producers—meaning consumers are more willing to take on a price increase—they will bear a greater share of the tax burden. Conversely, the more responsive a market participant is to changes in price, the less likely they are to bear the excess burden of a tax. A common illustration of this is the long-run burden of the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , which falls hardest on the least mobile (responsive) factor in the economy—typically workers. If a business decides to invest elsewhere because of the corporate income tax, perhaps because the result is customers deciding to purchase from a competitor, workers generally cannot pick up and move as well.

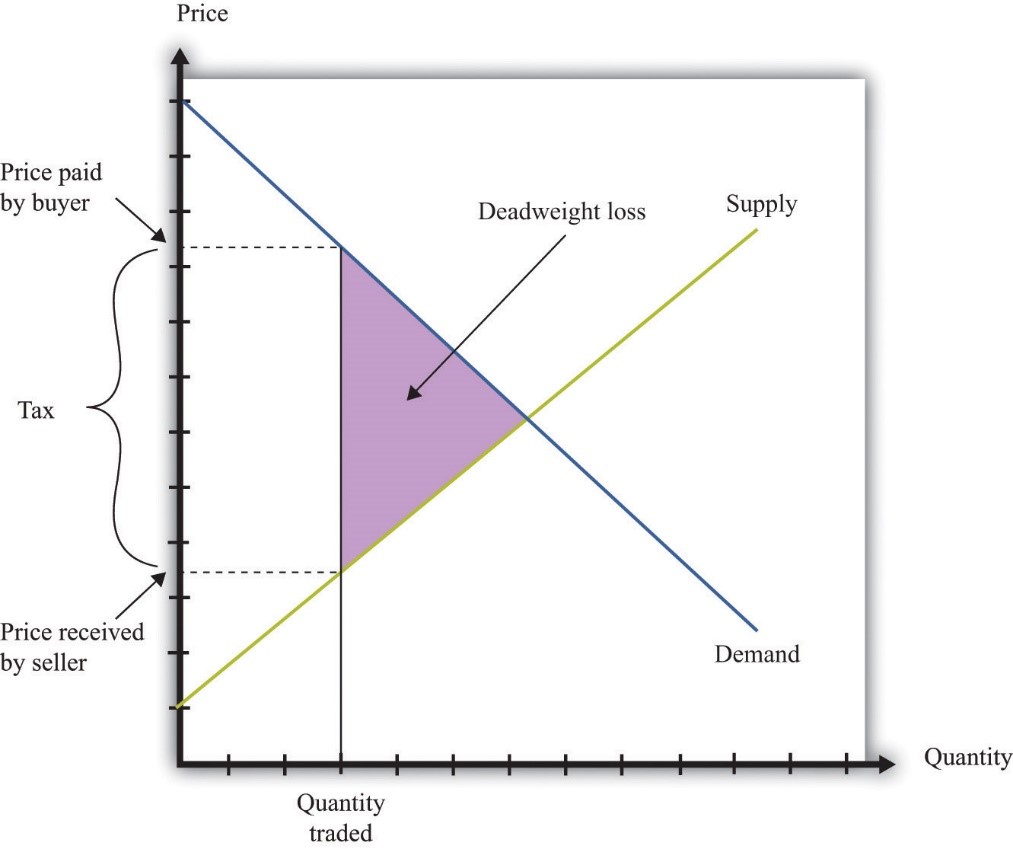

Graphically, this is illustrated in the figure below, where the tax wedgeA tax wedge is the difference between total labor costs to the employer and the corresponding net take-home pay of the employee. It is also an economic term that refers to the economic inefficiency resulting from taxes. —the deadweight loss—is represented by the purple triangle. The downward sloping blue line is the consumer’s demand curve and the upward sloping yellow line is the producer’s supply curve. Without a tax, the market clearing price and quantity of the good would occur where these two lines meet. However, the imposition of a tax means the consumer has to pay more for the good, the producer receives less for the good, and fewer goods are sold. The tax wedge is the activity that doesn’t occur, or the difference between these two scenarios.

Source: Saylor Academy, “Efficiency and Deadweight Loss,” Figure 17.9, “Tax Burdens,” 2012, https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_microeconomics-theory-through-applications/s21-11-efficiency-and-deadweight-loss.html

Mathematically, if a tax rate is doubled, its deadweight loss will quadruple—meaning the excess burden will increase at a faster rate than revenue increases. It is important to not only consider the change in revenue a tax increase would lead to, but also the increased deadweight loss the tax increase would cause.

Deadweight loss effects demonstrate why policymakers should pursue a more efficient tax code to achieve distributional objectives, rather than pursuing high tax rates that create disproportionately high economic costs. Policies such as broadening the base, lowering rates, and limiting deductions and exclusions, rather than policies to raise income tax rates to higher levels, would result in less loss of economic efficiency. If policymakers conclude that new revenue is needed, they should consider the deadweight loss of different tax policy options.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe