A bill that would prohibit the sale of flavored tobacco and nicotine products, HB22-1064, is moving through the Colorado legislature, which undoubtedly would have a significant impact on the revenue from taxes levied on those products.

Flavored tobacco and nicotine products make up a significant portion of the market: over 20 percent of cigarettes and other tobacco products and over 70 percent of non-tobacco nicotine products. The bill also bans all sale of products with synthetic nicotine. Prohibition would take effect in January 2024.

If the bill passes and Colorado shares Massachusetts’ experience, the state could lose approximately $84 million when compared to the projected revenue for the first full year following prohibition (calendar year 2024). The decline is pretty evenly split between decreases in cigarette taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenue and revenue from other tobacco and nicotine products. This revenue is earmarked for health-care spending, transfers to local governments, preschool programs, and other education spending. According to the bill’s accompanying initial fiscal analysis, the Preschool Programs Fund stands to lose over $20 million in funding. This money will either have to be made up with general fund revenue or through higher taxes on the remaining volume. The latter option is not particularly attractive as it would create issues of its own.

In an analysis of the introduced bill, the state assumes a smaller impact on volumes, and projects a loss of $37 million in fiscal year 2022. They assume that roughly two-thirds of consumers will switch to non-flavored and taxed products, but this was not the result in the only other state, Massachusetts, which has imposed flavor prohibition. In Massachusetts, approximately 70 percent of the flavored volume disappeared, with sales shifting to other states and presumably to illicit markets.

Since some flavored products may still be available in age-restricted stores (stores that require every consumer to show proof of age before entering), the revenue hit could be less than in Massachusetts. If the experience is similar to Canada, where flavored products are still available at First Nation territories, Colorado should expect to lose about 40 percent of the flavored volume or about $48 million.

Whether the final revenue decline will be closer to $37 million or $85 million depends on the accessibility of legal flavored products. The proposed complicated and burdensome licensing requirements to continue to sell flavored products is likely to limit the access—retailers must, for instance, submit monthly reports of all consumer purchases. Moreover, every retailer of flavored products runs the risks of getting investigated if one of their products finds its way into the hands of an underage person. Under an amendment to the legislation, all packs of cigarettes and vape liquid must carry a unique identifying number, and this number will be used to investigate the retail location that sold it in the first place. States certainly have a vested interest in keeping such products out of the hands of minors, and going after any retailers which make illegal sales, but there are certainly ways that a minor gets their hands on a pack of menthol cigarettes that don’t involve them being the purchaser.

It stands to reason that if consumption truly disappeared as a result of prohibition, and taxes on tobacco and nicotine products were genuinely intended to account for the harms caused by the products, no one would be worried about such a loss in revenue—if consumption is gone, so are the societal costs associated with consumption. Unfortunately, flavor bans are basically literal laws of unintended consequences. In the one state with available data, Massachusetts, consumption has not disappeared; sales to Massachusetts residents have merely moved out of the state. There is nothing to suggest that a similar situation would not occur in Colorado.

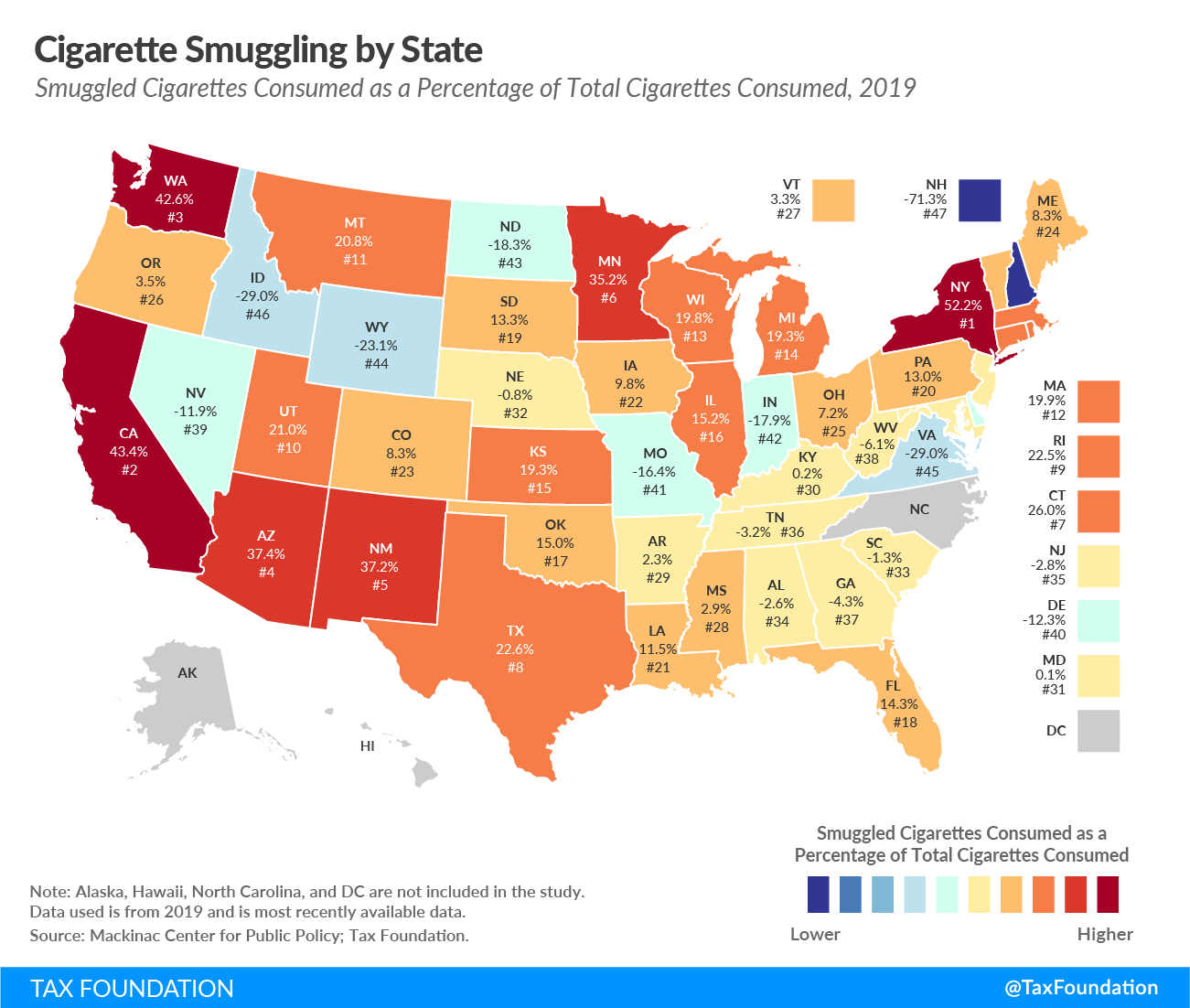

It is far more likely that consumption shifts from legal sales to a combination of casual and organized smuggling. Colorado currently has manageable levels of cigarette smuggling, but this would likely change post-prohibition. Neighboring Utah and Kansas both have relatively high levels of smuggling, which means that smuggling routes are already established in the region.

More smuggling means increased criminality and enforcement costs for the state government, something the state has successfully combated in the past decade by allowing sales and consumption of previously prohibited products.

The main reason for this bill is a desire to protect youth from nicotine addiction. This is, of course, a laudable goal that everyone supports. It is less clear, however, that flavor bans will do much to accelerate an already impressive and underpublicized trend: only 1.5 percent of middle schoolers and high schoolers smoked in the last 30 days, and 7.6 percent of the same group vaped. In 2019, the percent of high schoolers who had vaped in the past 30 days was 27.5, and 5.8 percent had smoked in the same period. A mere 13.5 percent of minors who have ever vaped report flavors as their reasons for trying vaping.

Unfortunately, efforts like this one harm adult smokers’ ability to switch from combustible cigarettes to less harmful tobacco and nicotine products. The Colorado bill bans all non-tobacco-flavored tobacco and nicotine products, but adult consumers overwhelmingly prefer non-tobacco-flavored products, so limiting access to these products could harm smoking cessation efforts.

Lawmakers in Colorado, and in the several other states considering flavor bans, should think twice before following in the footsteps of Massachusetts. A statewide ban on flavored tobacco products is more than likely to costs millions of dollars, increase smuggling, and have a negligible effect on public health. Moreover, the federal government is currently reviewing product standards for both vapor products and flavored cigarettes. It would be appropriate to allow that process to conclude before the state takes any further action.