Over the weekend, Governor Jeb Bush suspended his bid for the Republican presidential nomination. As journalists and pundits take stock of the campaign, tax policy wonks have an opportunity to look back at the Bush taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. plan and some of the interesting proposals included in it.

In many respects, Jeb Bush’s tax plan was quite similar to those of his opponents. Like most of the Republican tax proposals this election cycle, the Bush tax plan lowers tax rates on individuals and corporations, eliminates the AMT and the estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. , moves to a territorial system, and allows businesses to fully expense investment costs.

However, the Bush tax plan also included several proposals that stood out from the rest of the Republican field. Here are three of the most interesting ones:

1. Capping the tax value of itemized deductions at 2 percent of income

Almost every tax reform plan these days includes some limit on itemized deductions, and for good reason. Itemized deductions narrow the federal tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , add complexity to the tax code, mostly benefit high-income taxpayers, and lead to lower federal revenues. Furthermore, some itemized deductions are just poor tax policy, such the deduction for state and local taxes.

However, Bush’s tax plan goes farther than almost all of his opponents’ in limiting itemized deductions. The Bush plan would not allow a household to save more than 2 percent of its income by claiming itemized deductions. In more technical terms, it would cap the tax value of itemized deductions at 2 percent of adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” .

The table below shows how this proposal would work. Currently, a household making $600,000 that claims $100,000 in deductions would be able to reduce its tax bill by $39,600. Under the Bush plan, the household would only be able to reduce its tax bill by 2 percent of its income, or $12,000.

|

Value of $100,000 of Itemized Deductions to a Household with $600,000 in Income |

|

|

Current law |

$100,000 × 0.396 = $39,600 |

|

Bush plan |

$600,000 × 0.02 = $12,000 |

|

Note: To simplify matters, this calculation assumes that the household is at least $100,000 over the threshold for the top income tax bracket. |

One consequence of this proposal is that far fewer households would itemize deductions under the Bush plan. According to the campaign, limiting itemized deductions and expanding the standard deduction would reduce the number of itemizers by almost 80 percent. In other words, the Bush tax plan would mostly put an end to the use of itemized deductions, through one simple rule.

2. Flipping the tax treatment of interest

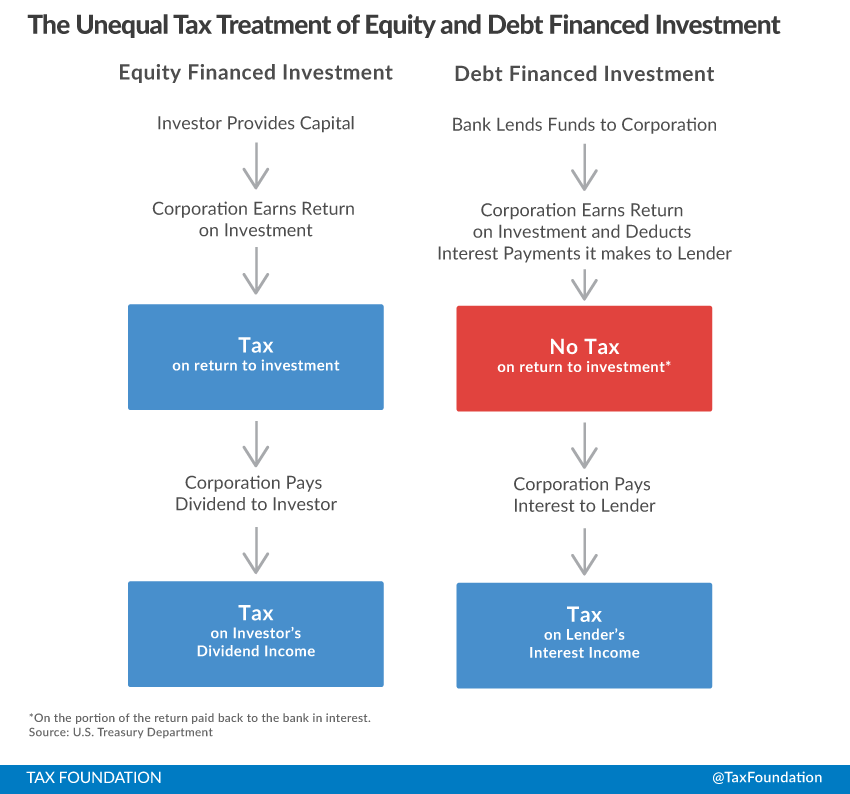

The Bush tax plan tackles one of the most long-standing issues in the corporate tax code: the unequal treatment of debt and equity financing.

In general, there are two ways that a business can finance its operations: by issuing stocks (equity) or by taking out a loan (debt). For some time, the U.S. tax code has given more favorable treatment to debt financing than equity financing. Specifically, businesses are able to deduct their interest payments to debt-holders, but are not able to deduct their dividend payments to stockholders. Even though dividends are taxed at a lower rate on the shareholder level than interest, this is not sufficient to make up for the favorable tax treatment of debt.

To equalize the tax treatment of debt and equity, the Bush tax plan would reverse the way that the tax code treats interest. Under the Bush plan, businesses would no longer be able to deduct interest payments, just as they are unable to deduct dividend payments. Meanwhile, individuals that earn interest would pay the same lower rate on their interest income as they do on dividend income. In simpler terms, the Bush plan would increase taxes on interest paid by businesses, and decrease taxes on interest received by individuals.

This proposal (which we at the Tax Foundation affectionately refer to as “the interest flip”) would actually raise quite a bit of tax revenue. A sizeable share of business debt is held by tax exempt-organizations, such as university endowments, who are generally not required to pay taxes on the interest they receive. Because the Bush plan would tax all interest paid by businesses, it would also tax interest paid on the debts held by tax-exempt organizations, increasing federal revenues.

So, in addition to ending the debt-equity distortion in the federal tax code, the “interest flip” would also have helped to pay for Bush’s other proposed tax cuts.

3. Allowing secondary earners to file separately

Finally, the Bush tax plan included an ambitious proposal to encourage work among secondary earners: individuals in a married couple that earn less than their spouses.

To illustrate the problem that the Bush plan addresses, we can imagine a married couple where one spouse (the primary earner) earns $200,000 and the other spouse (the secondary earner) earns $25,000.

- If the couple chooses to file separately, the primary earner would likely fall into the 33 percent bracket and the secondary earner would likely fall into the 15 percent bracket.

- If the couple chooses to file jointly, both the primary earner and the secondary earner would likely fall into the 28 percent bracket.

If the couple chooses to file jointly, the secondary earner’s marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. would rise from 15 percent to 28 percent. Higher tax rates for secondary earners likely lead to lower work force participation, as research shows that decisions about work among secondary earners are particularly sensitive to taxes.

To address this problem, the Bush tax plan would allow secondary earners within a marriage to file a separate tax return, while continuing to provide primary earners with all of the tax benefits of filing jointly. In effect, the Bush proposal would transform the way that joint filing works, in order to eliminate the high marginal tax rates on secondary earners that file jointly.

All in all, while the Bush campaign has ended, the tax policy community can still take lessons from the Bush tax plan and the interesting proposals included in it.

Share this article