A little over a week ago the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) released a report on the relationship between corporate taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform and wage growth. Later that week, Kimberly Clausing and Edward Kleinbard from Vox wrote a response in which they criticized the report’s key findings by drawing on the United Kingdom’s recent experience with corporate tax reform. However, Clausing and Kleinbard are incorrect to claim that the experience of the UK shows that corporate tax rate reductions do not affect wage growth.

In their argument, Clausing and Kleinbard contrast the CEA’s predictions that a corporate rate cut would lead to wage growth to the results of the UK’s recent experiment with corporate tax reform. Surprisingly, as the UK cut its corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate, the country’s inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. -adjusted median wage also dropped. This counterintuitive result would imply that reducing corporate tax rates might lead to lower wages, a notion at odds with most conventional literature on corporate incidence.

However, Clausing and Kleinbard’s argument relied heavily on the assumption that the only meaningful change to the UK’s corporate tax structure in recent years was the reduction of the corporate income tax rate. In fact, there is reason to believe that other structural changes to the UK’s corporate tax could have been responsible for the fall in wages.

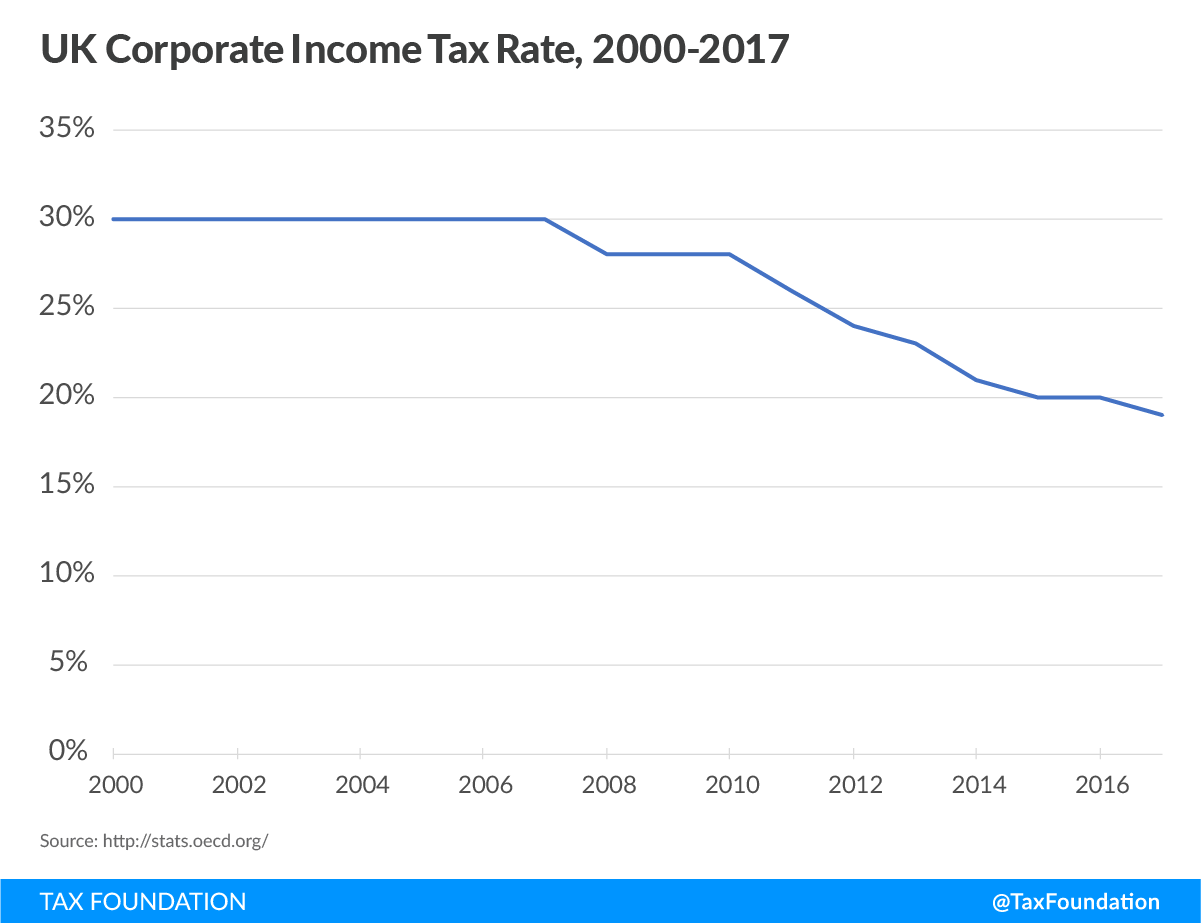

Over the past 10 years, the UK has lowered its corporate income tax rate from a high of 30 percent in 2007 to 19 percent in 2017. In addition, the UK moved to a territorial tax systemA territorial tax system for corporations, as opposed to a worldwide tax system, excludes profits multinational companies earn in foreign countries from their domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. which exempts foreign corporate income from domestic taxation, and enacted a “patent boxA patent box—also referred to as intellectual property (IP) regime—taxes business income earned from IP at a rate below the statutory corporate income tax rate, aiming to encourage local research and development. Many patent boxes around the world have undergone substantial reforms due to profit shifting concerns. ,” which provides a special lower rate on profits attributable to intellectual property.

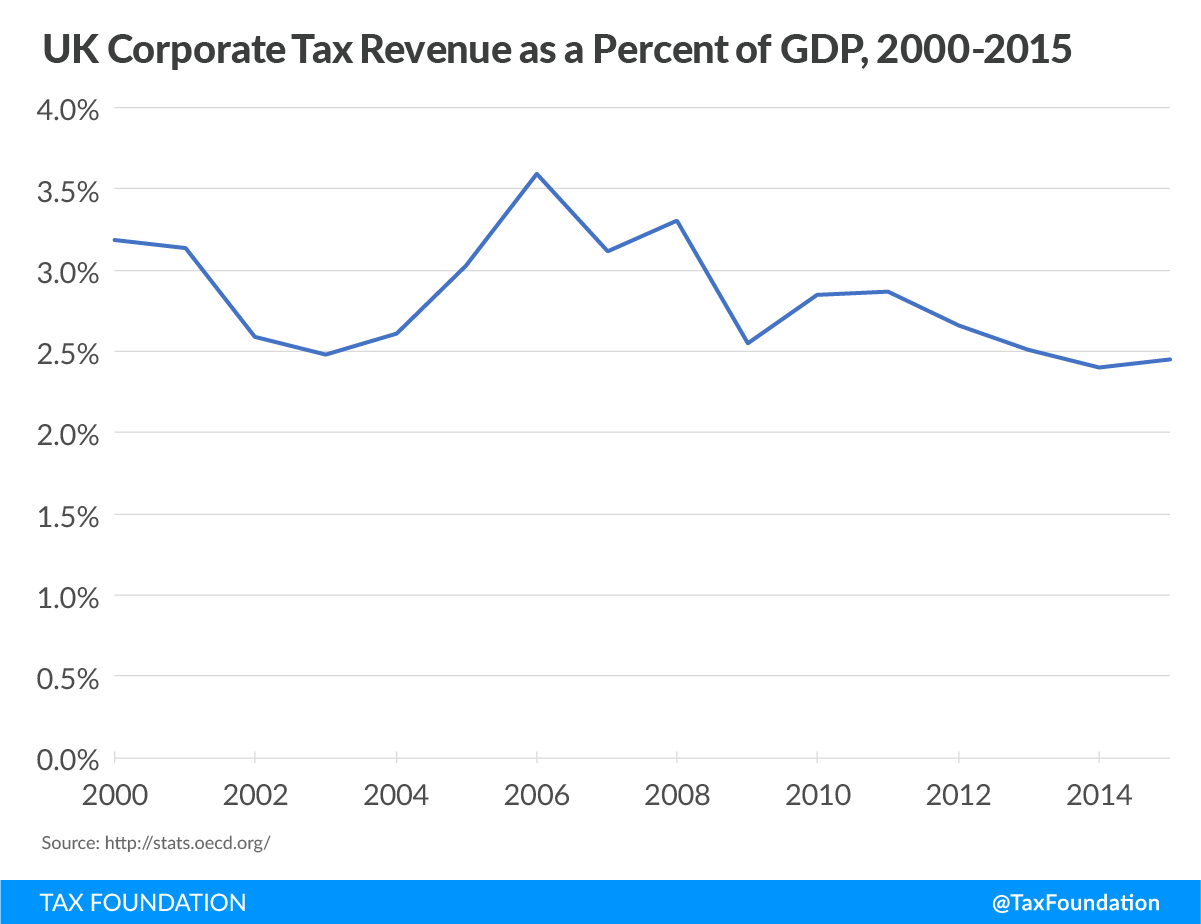

Despite this, the UK’s corporate tax revenue as a percent of GDP from 2000 to 2015 remained roughly consistent between 3.5 percent and 2.5 percent. This has led some analysts to incorrectly believe that the UK’s corporate tax cut paid for itself, whereas the UK actually paid for its corporate rate cut by broadening its corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. . The UK paired its rate cut with lengthened asset lives for capital investments and anti-base erosion rules. These changes ultimately helped pay for the corporate rate reduction.

The most notable change to the UK’s corporate tax base was in its treatment of capital expenditures. Corporations that make capital expenditures are required to deduct the costs of these investments over time, through a provision known as depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. deductions. Depreciable asset lives vary by asset type, and countries allow different lengths of time to write off such investments. Generally, when asset lives become longer, corporations end up paying more tax on their additional investments — the value of depreciation deductions are reduced over time, due to inflation and the time value of money.

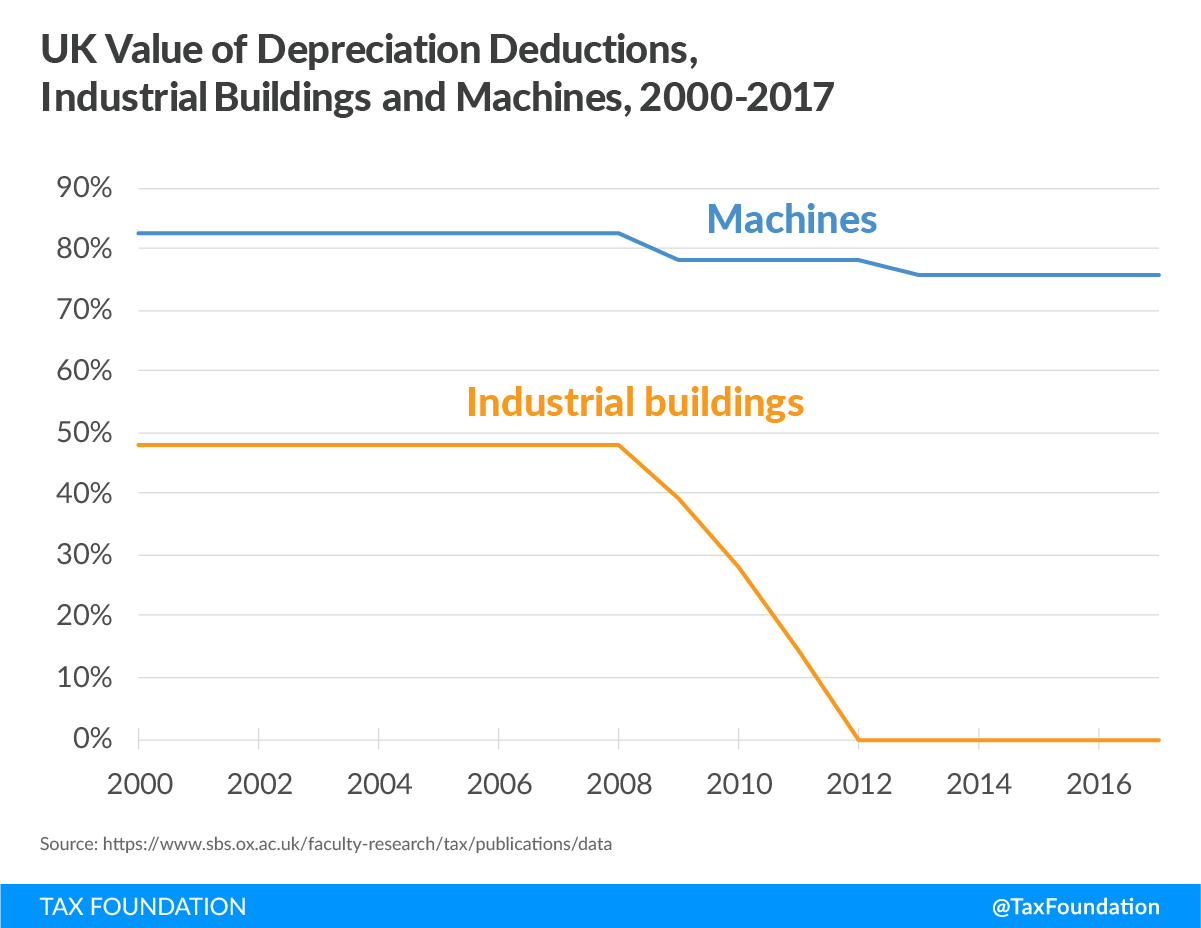

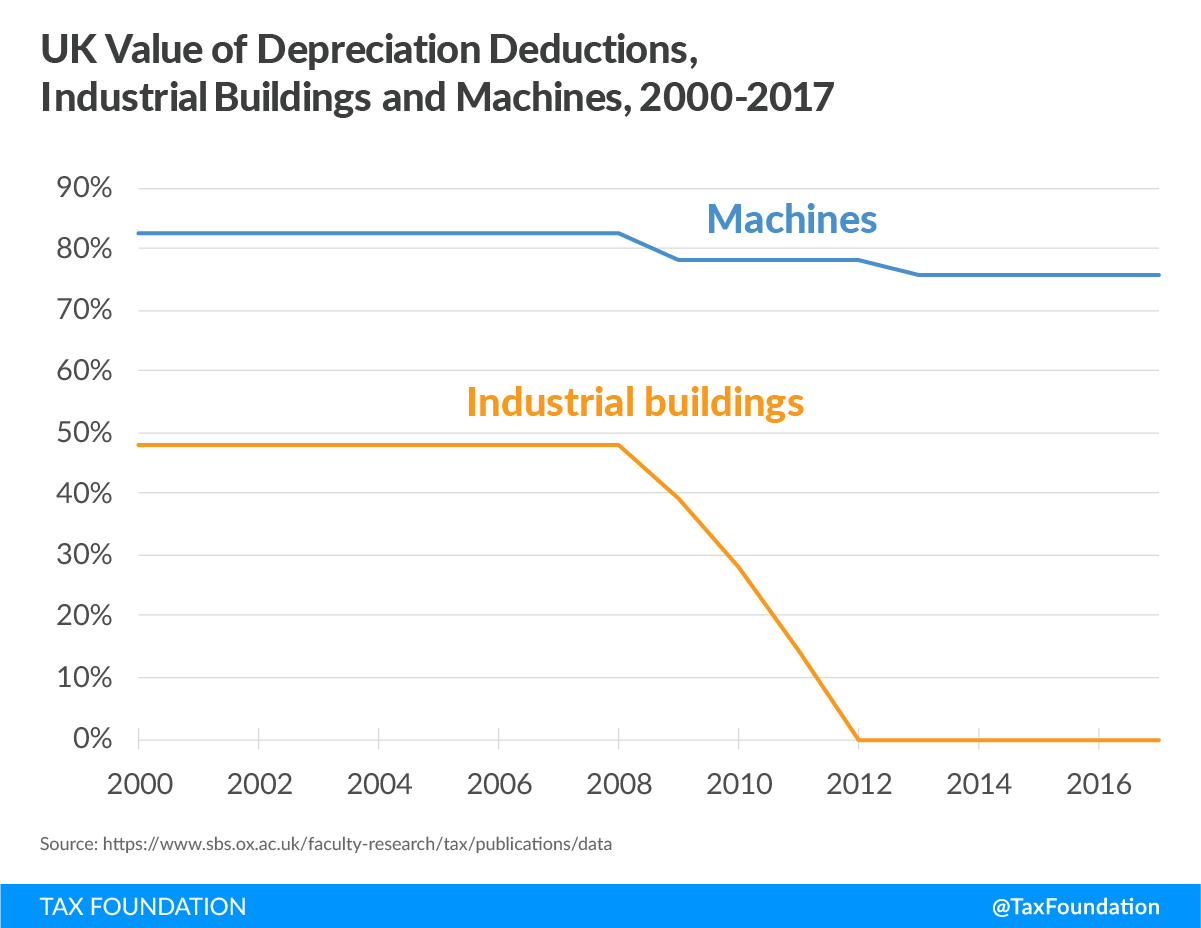

Between 2008 and 2013, the United Kingdom reduced the value of depreciation deductions for machines and industrial buildings. The present value deduction (the percent of the cost of an investment a company can deduct over its life) for machines fell from 83 percent to 76 percent between 2008 and 2013. Over the same period, the value deduction for industrial buildings fell from 48 percent to zero. This means that corporations in the UK cannot write off the cost of investing in buildings at all!

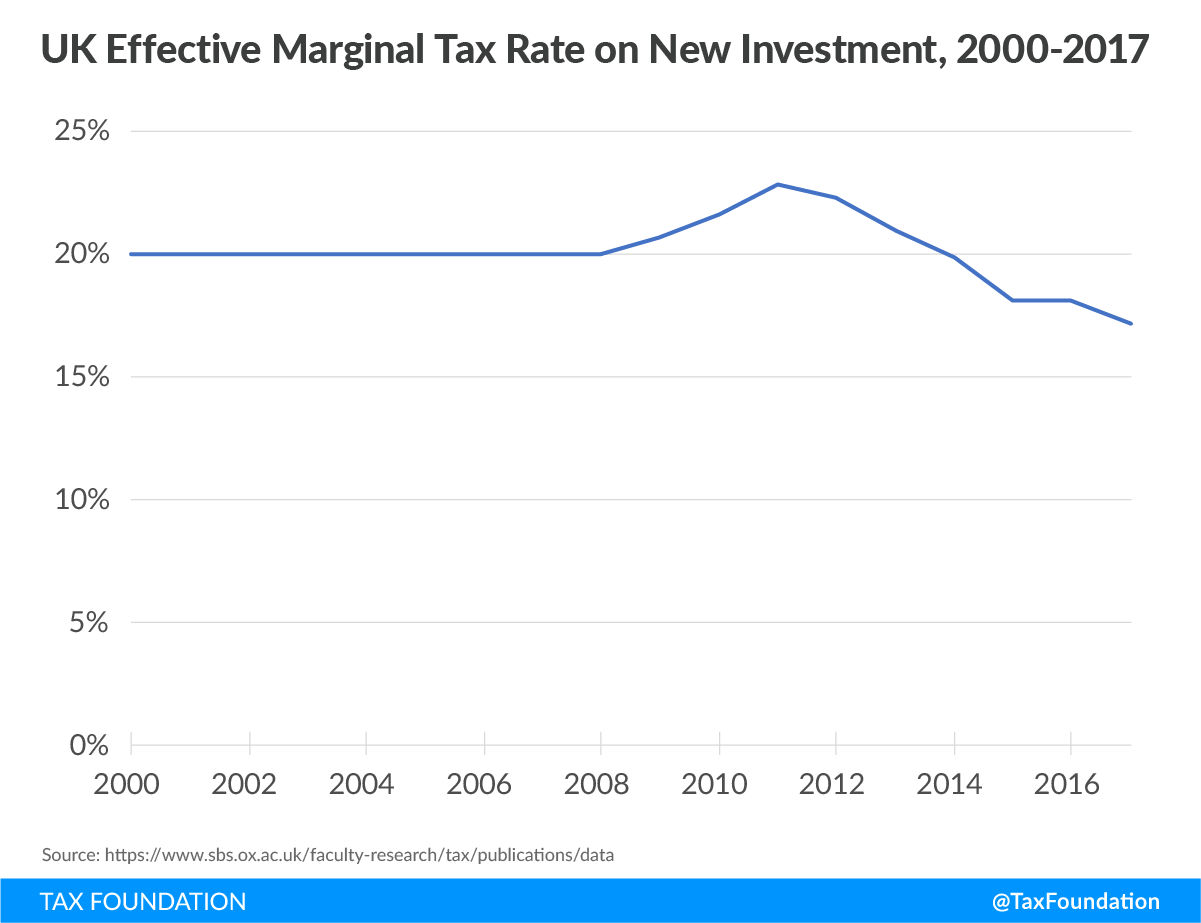

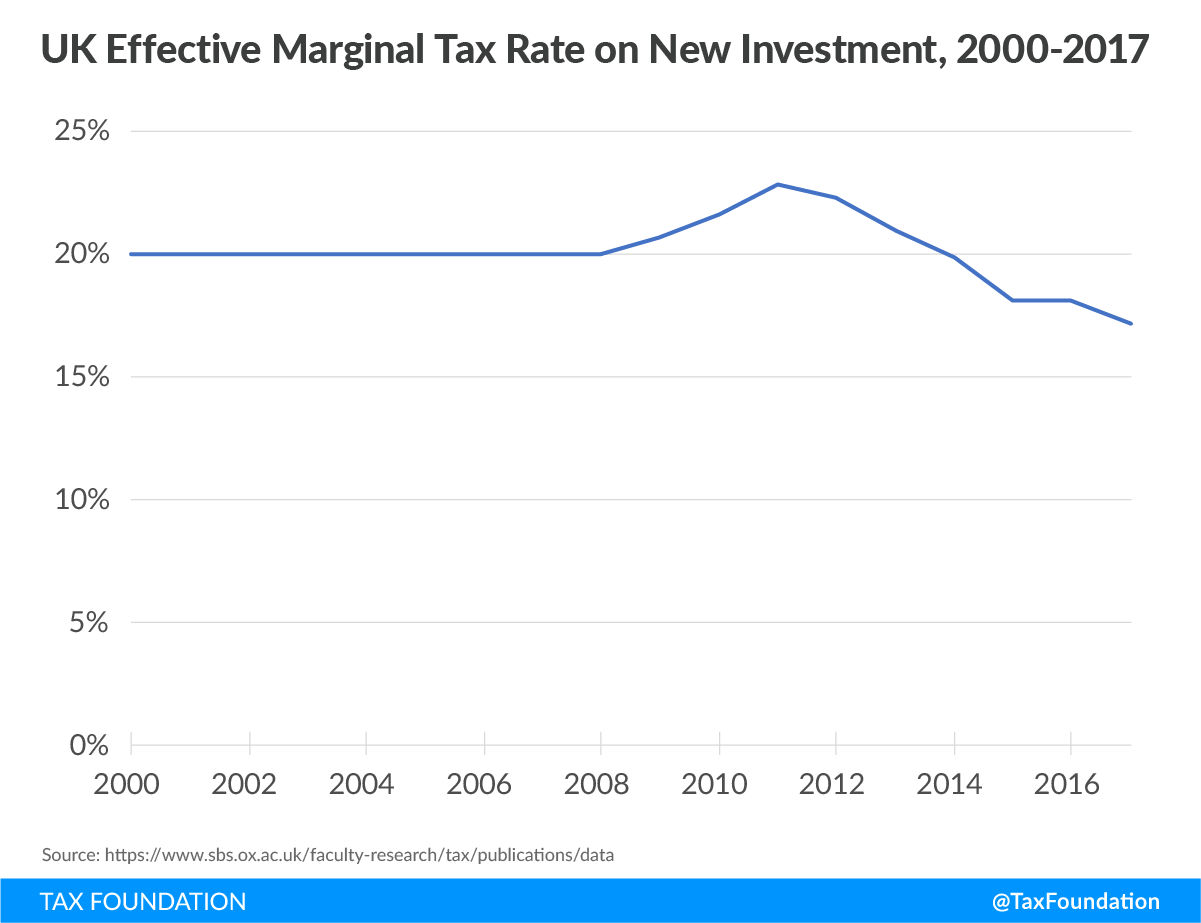

While these changes to the UK’s corporate tax base help offset the revenue impact of cutting its corporate tax rate, they also potentially offset the economic benefits of a lower statutory rate. The length of time an asset can be written off has a large impact on the tax burden on marginal investments. Lengthening asset lives can increase the marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. on investment, even as the statutory tax rate falls. According to the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, the UK’s effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) on new investment climbed from around 20 percent in 2007 to 23 percent in 2010, even as the statutory corporate rate declined by five percentage points. Overall, the EMTR only fell by three percentage points from 2007 and 2017, from 20 percent to 17 percent, while the statutory corporate tax fell by 10 percentage points.

When taking a closer look at the UK’s recent corporate tax reform experiment, it becomes clear that there was significantly more at work than just a simple rate cut. Increasing the effective marginal tax rate on new investments could have had a negative effect on wages, potentially offsetting the positive effects from the corporate rate cut.

Since corporate rate cuts are rarely ever self-financing, finding effective pay-fors are among the most important policy considerations. With policymakers in the United States and abroad seeking to lower overall corporate income tax rates, they should take extra care to ensure that their base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. strategies are neither distortive nor anti-growth.

Share