A joint constitutional convention of Massachusetts lawmakers has voted 147-48 to approve H.86, dubbed the Fair Share Amendment, to impose a 4 percent income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. surcharge on annual income beyond $1 million. The new tax would be levied in addition to the existing 5.05 percent flat rate, bringing Massachusetts’ total top rate to 9.05 percent. Supporters of the tax say it would generate as much as $2 billion of annual revenue to be earmarked for public education and the improvement and maintenance of infrastructure.

The legislature’s approval of H.86 kicks off the second attempt in as many years to enact a millionaires’ tax. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court struck down a citizen petition to implement the same tax in June of 2018. Massachusetts requires legislatively-referred constitutional amendments be passed in consecutive sessions, meaning that the same measure would need to be approved in the 2021-2022 legislative session before it would be sent to voters in November of 2022.

The millionaires’ tax, though targeted at a wealthy minority of tax filers in the Bay State, would cause broader harm to Massachusetts’ tax structure and economic climate. It would eliminate Massachusetts’ primary tax advantage over regional competitors, provide an unstable revenue source that is ill-suited for funding core public services, hit a significant portion of Massachusetts’ pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income, and increase the incentive for tax avoidance through personal and business relocation.

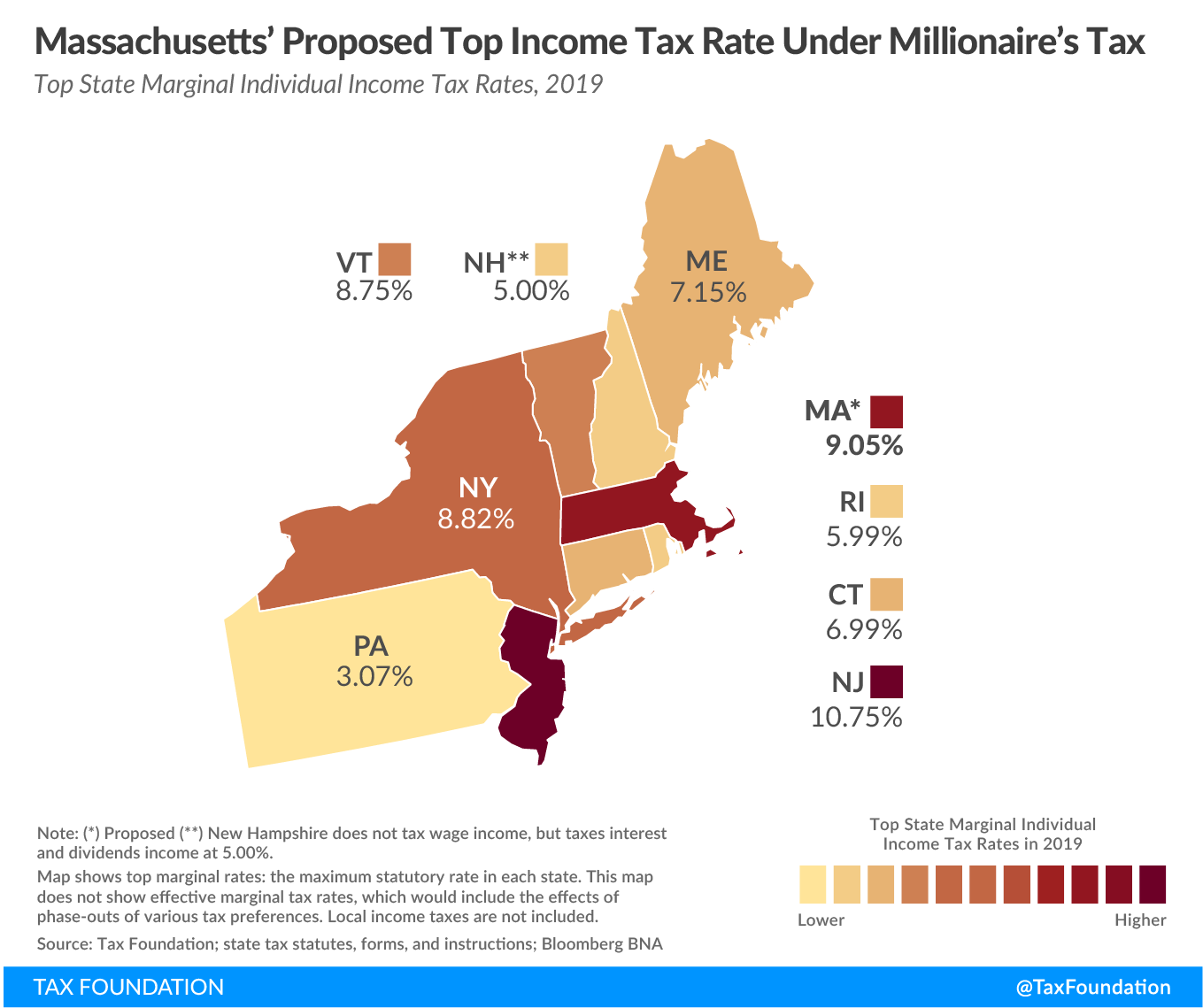

The Bay State’s low, flat income tax on individuals and pass-through businesses is the most competitive element of its tax code, giving the Commonwealth a clear strength compared to surrounding states and regional competitors. Income tax rate reductions in recent years have helped shed the moniker of “Taxachusetts” while setting up the Bay State to be a beneficiary of harmful tax rate increases in surrounding states. However, a 9.05 percent top rate would be uncompetitive even in a high-tax region.

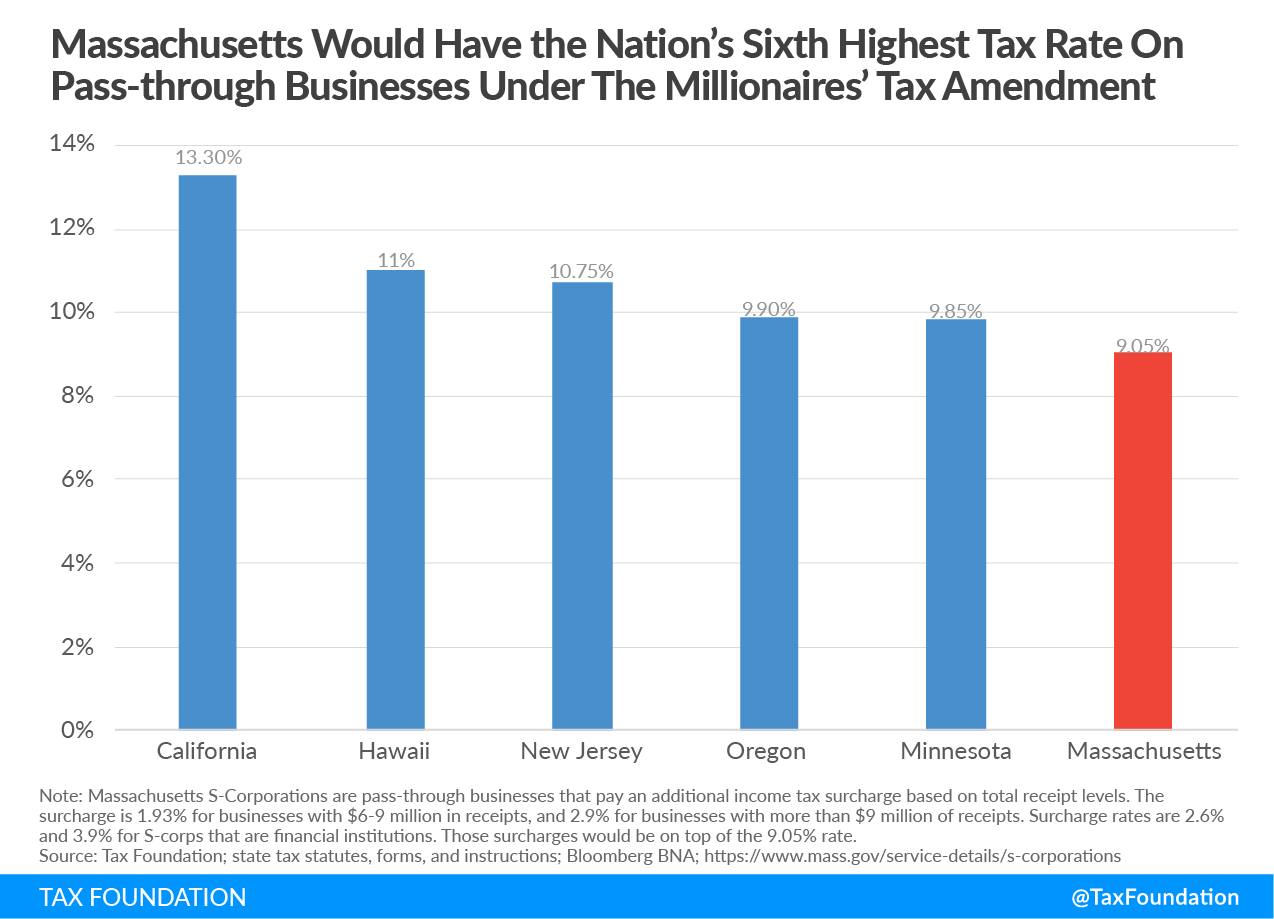

The amendment would hit Massachusetts pass-through businesses with the sixth-highest tax rate of any state. The higher rate would be paid by roughly 11,000 Massachusetts business tax returns that account for more than 62 percent of all Massachusetts’ pass-through business income, according to 2016 IRS data.

Supporters of the millionaires’ tax proposal cite income inequality as one justification for the tax. However, research points to potential job losses and the outmigration of high earners as a result of high state income tax rates. The millionaires’ surcharge would fund infrastructure and education, though the amendment does not specify that the new dollars would be added on top of baseline revenue levels. A tax on income beyond $1 million is a poor revenue structure to fund core government services like education and transportation. Income beyond $1 million is largely made up of pass-through business income, dividends, interest, and capital gains, which are highly volatile through the business cycle. The amendment also creates a marriage penaltyA marriage penalty is when a household’s overall tax bill increases due to a couple marrying and filing taxes jointly. A marriage penalty typically occurs when two individuals with similar incomes marry; this is true for both high- and low-income couples. —the $1 million income threshold does not vary based on filing status.

Two studies published this April serve as a warning of the economic losses and tax inefficiencies engendered by high tax rates. “State Taxation and the Reallocation of Business Activity: Evidence from Establishment-Level Data,” published in the University of Chicago’s Journal of Political Economy, estimates that a 100 basis point (1 percent) change in the personal income tax rate in a state corresponds with up to a 0.4 percent change in the state’s count of pass-through business establishments and 0.2 percent change in employment for multistate pass-through firms. “Taxation and Migration: Evidence and Policy Implications” was also published in April, through the National Bureau of Economic Research. It found that high-income workers and professions that are not tied to a location can be quite responsive to taxation when deciding where to locate.

Massachusetts’ tax code already incentivizes tax avoidance for higher-net-worth residents. The Bay State’s estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. kicks in after a relatively low $1 million exemption in estate value, which is the lowest threshold of any of the 12 states that impose an estate tax. A millionaires’ tax would largely fall upon an overlapping population of taxpayers, thus increasing the incentive for tax relocation.

Relocation options are obvious for Massachusetts’ mobile high-income earners. According to the past 25 years of IRS taxpayer migration data, the two states that see the greatest net gains of Massachusetts income are New Hampshire and Florida—both states that do not levy tax on wage income. (New Hampshire taxes dividend and interest income at 5 percent.)

Perhaps equally concerning from a governance perspective is that policymakers could not easily adjust course on tax policy if they find that the new tax surcharge hurts the dynamism of the Massachusetts economy. Proponents of the amendment rejected a proposal to allow the legislature to set the surcharge by statute at a rate of up to 4 percent. Thus, the 4 percent surcharge would be locked into the constitution and could not be changed by statute without a new constitutional amendment.

Massachusetts’ millionaires’ tax proposal would hurt the Bay State’s economic vitality. It would cede Massachusetts’ core tax strength compared to regional competitors, hit the Commonwealth’s most successful pass-through businesses, provide an unstable source of funding for core government services, and incentivize tax avoidance and relocation.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe