House Democrats’ newly released $3.5 trillion tax legislation includes a taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. increase on tobacco, nicotine, and vapor products levied on tobacco manufacturers. But ultimately it would fall heavily on tobacco consumers—many of the group that earns less than $400,000 that President Biden pledged would not see a tax increase. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, this increase would contribute $96 billion to the budget.

If the administration considers a tobacco tax hike a tax on consumers as it did for a gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. hike, the proposal may be short-lived.

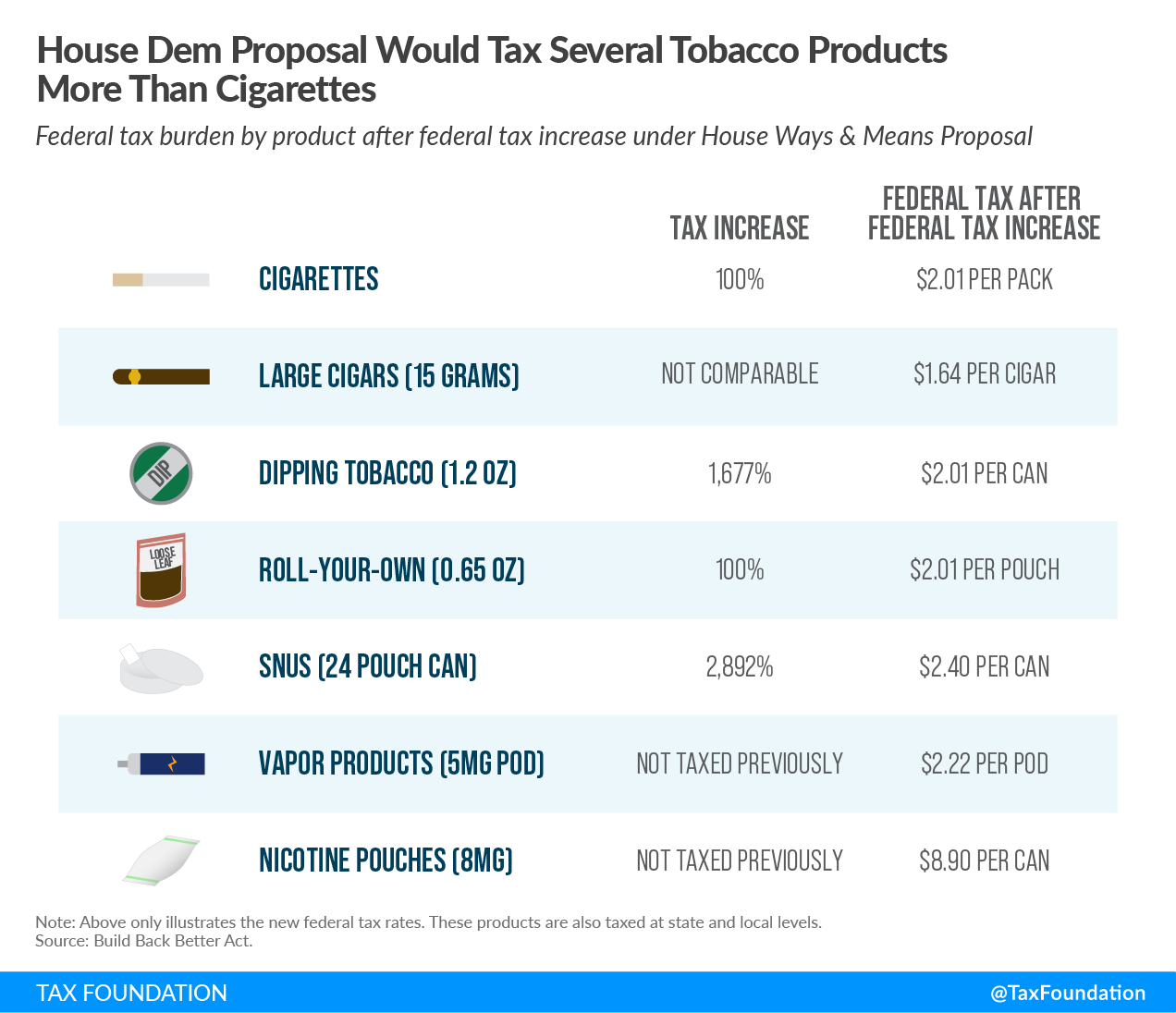

The tax would raise the almost $100 billion by doubling rates on cigarettes and increasing rates on all other tobacco and nicotine products to achieve parity with the new rate on cigarettes. Doubling the cigarette tax rate yields a high rate, but tax parity across all products results in increases on other tobacco products that are significantly higher.

The rate on chewing tobacco increases more than 2,000 percent, and the rates on pipe tobacco and snuff over 1,600 percent each. Vapor products, which have not been taxed at the federal level thus far, would be taxed at a rate of $100.66 per 1,810 mg of nicotine. That equals a federal tax on a regular pod-based product of roughly $2.25 per pod—more than the new federal $2.01 rate on a pack of cigarettes).

The legislative intent of achieving parity across a wide product portfolio containing non-combustible and non-tobacco products would hurt consumer access to harm-reducing products. While more research relating to the potential harm-reduction qualities of vapor and nicotine products is needed, the current consensus is that these products are less harmful than traditional combustible tobacco products. Public Health England, an agency of the English Ministry for Health, concludes that vapor products are 95 percent less harmful than cigarettes.

The federal government recognizes the different harm profiles of tobacco products. A few product types have been authorized as Modified Risk Tobacco Products (MRTP) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which means they have been proven less harmful than existing tobacco products. Excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. es should, ideally, reflect this difference in harm. One way to do this is to include triggers that cut the tax rate for products which obtain MRTP orders—something several states already do.

Since tobacco and nicotine products are substitute goods, ignoring the issues surrounding harm reduction could lead to unintended consequences. A recently published study concluded that taxes on vapor products lead to increases in youth tobacco use. Prior studies have shown similar effects on adult users.

While $96 billion is substantial revenue, taxes on tobacco and nicotine products should not be considered stable. Decades of declining use means that tobacco taxes generally raise less revenue with each passing year. In addition, the narrow tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. exposes the revenue to non-tax-related regulatory policy. For example, the FDA has recently announced its intent to ban the sale of menthol cigarettes nationwide. If the lesson of Massachusetts is any indication, such a ban, which would criminalize the sale of over a third of the current national market, could have a massive impact on revenue generation. Moreover, the FDA is in the process of reviewing authorization applications for all vapor products. As of today, they have denied over 90 percent of the applications.

Doubling the cigarette excise tax rate moves the rate far beyond internalizing externalities. It is not aligned with the health costs of smoking and is not intended to be. It is, primarily, a source of additional revenue, and must be evaluated in those terms.

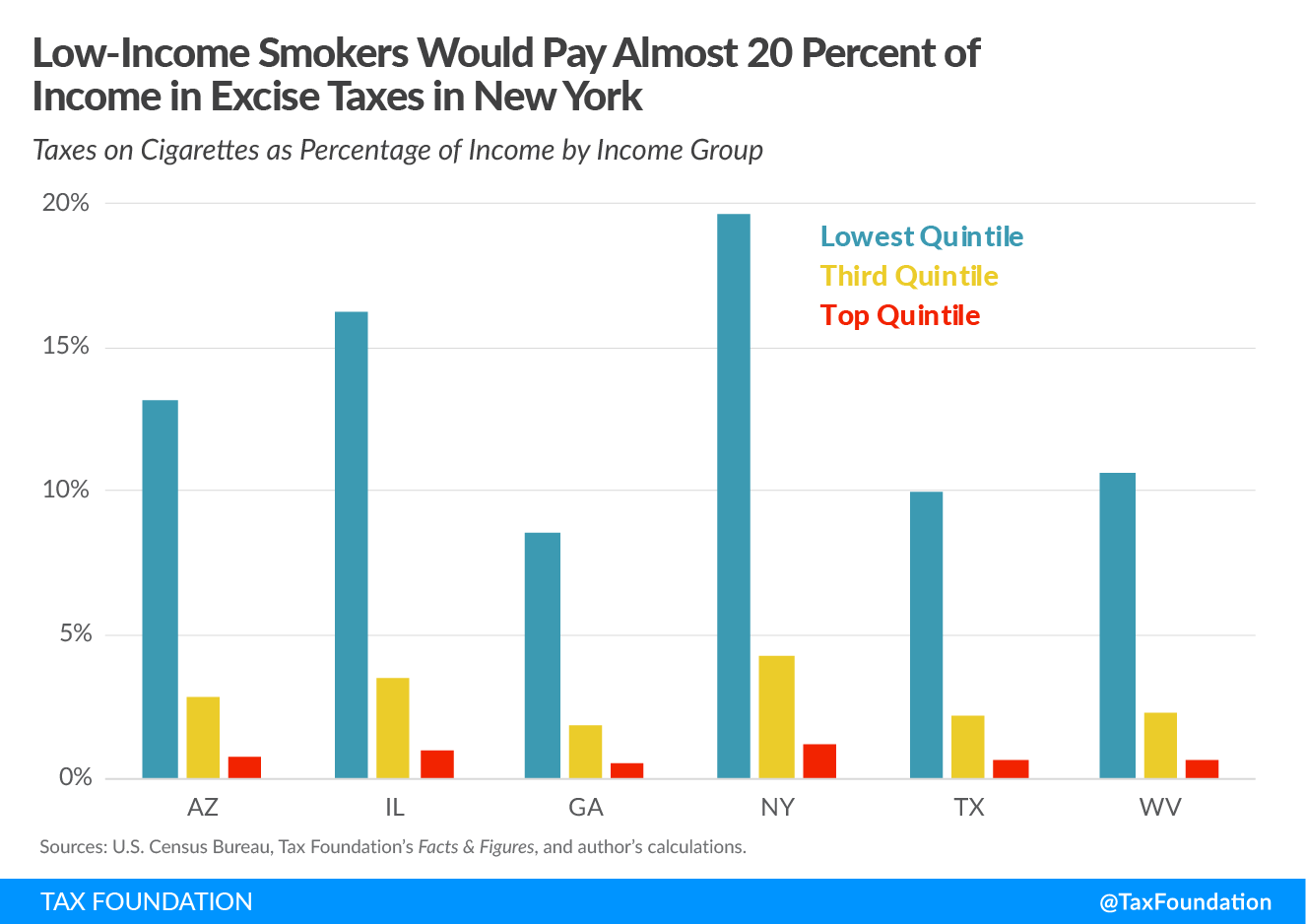

As a source of general fund revenue, the tax is exceedingly regressive. The vast majority of smokers have lower incomes, and tobacco is one of the few goods that have an inverse relationship with income in that consumption increases as income decreases. Today, at a national level, a pack-a-day-smoker making $15,000 a year pays almost 10 percent of their income in tobacco taxes (state and federal). The proposed increase takes that figure to 12 percent. For someone making $35,000 that’s 4.1 percent today and 5.2 percent after the tax increase. Of course, these are national averages, and there is significant variation from state to state.

The price of cigarettes may increase markedly, but the price of other tobacco could be impacted to a much larger degree. In Massachusetts, for example, taxes for a can of dip would increase by 1,677 percent. Increasing costs can exacerbate issues surrounding illicit trade (which could reduce state tax collections). Illicit trade with tobacco products is a global multibillion-dollar operation, which often involves some of the world’s worst criminals. In the U.S., the states that suffer the most from smuggled tobacco products are those where cheaper products are easily available.

In addition to the lack of revenue stability and disregard for harm reduction, the bill has major issues surrounding tax base design—most notably for the vapor tax. Taxing vapor products based on nicotine is not desirable if the rationale for taxing involved considerations beyond mere revenue (and it should). Nicotine content alone does not determine nicotine absorption. Differences in electronic cigarette device design, as well as nicotine product design, have big implications for how much nicotine is absorbed by the consumer.

Taxing based on nicotine content would favor low-nicotine liquids and could encourage increased consumption in the quantity of liquid. For instance, a vapor pod that has a nicotine content of 3 percent and contains 1 ml of liquid would be taxed at $1.67, whereas a vapor pod that has a nicotine content of 5 percent and also contains 1 ml of liquid would be taxed at $2.78. It is even worse for other recreational nicotine products such as nicotine pouches. A can of non-tobacco-containing nicotine pouches with 20 pouches and 5 mg of nicotine per pouch would be taxed at $5.56 per can—over two and a half times higher than a pack of cigarettes.

Instead, a tax on vapor products (and other recreational nicotine products) should be based on quantity: a specific excise tax based on volume (e.g., a certain amount per ml) at a low rate is the most efficient way to design a tax on nicotine products as it is the most neutral. Legislators could consider establishing a tiered system, where open refillable systems are taxed at a lower rate than closed systems, with different rates designed to equalize taxation and keep it neutral, not introduce unnecessary disparities.

The level (dollar amount) of the excise tax should reflect the harm of nicotine products relative to traditional tobacco products. Recently, the Royal College of Physicians released a report recommending a tax of 5 percent relative to the tax on combustible tobacco. To illustrate how that would work in the context of this proposal: if a pack of cigarettes is taxed at $2.00, the vapor products tax should be $0.10 per pod for closed systems, since a pod is a substitute for one pack of cigarettes.

While it is uncertain if the president will oppose the proposed tax as a tax on people earning less than $400,000, there are plenty of other (and better) reasons to oppose the increase. Federal lawmakers should not consider tobacco excise taxes a stable revenue source for long-term spending, and they should remember the unintended consequences of such significant increases. Excise taxes are legitimate when certain negative externalities associated with a type of transaction or type of consumption can be identified, and they can work well to establish user-fee systems.

Lawmakers looking to generate stable revenue for general recurring spending priorities, however, should raise that through broad-based taxes at low rates instead.

Related Research

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe