Examining the EU Corporate Own Resources Proposal: Implications and Challenges

5 min readBy: ,In June, the European Commission proposed a new source of revenue as part of its second basket of own resources: a “temporary statistical own resource based on company profits.” This is an attempt to bolster the EU’s budget as it repays its debt. Previous proposals for new EU own resources have targeted narrower taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. bases, such as a financial transaction tax (FTT), digital levies (DSTs), or taxes on crypto transactions.

This own resource proposal is technically not a tax, but it would require EU Member States to adjust their fiscal policy (either increasing taxes or reducing spending) to pay the new amounts to the EU budget.

The proposal for a temporary measure is expected to be replaced by a possible contribution from the Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation (BEFIT) initiative. But what exactly does the Commission intend? What does it entail for Member States and the EU’s long-term budget and own resources?

Understanding the Proposal

This levy would require Member States to contribute 0.5 percent of the corporate capital income measure—gross operating surplus (GOS)—from financial and non-financial corporations to the EU budget. The Commission estimates that this initiative would generate EUR 16 billion (in 2018 euros) in revenue to support the EU’s long-term budget. According to the Commission, this is not a direct taxA direct tax is levied on individuals and organizations and cannot be shifted to another payer. Often with a direct tax, such as the personal income tax, tax rates increase as the taxpayer’s ability to pay increases, resulting in what’s called a progressive tax. on companies, nor would it increase companies’ compliance costs.

Currently, the European Union has three main sources of revenue—customs duties, contributions based on the value-added tax (VAT) collected by Member States, and direct contributions by EU countries (the “gross national income [GNI]-based resource”). In 2021, the Union also introduced a contribution based on non-recycled plastic packaging waste.

The GNI-based resource is the budget’s largest income source—amounting to around EUR 116 billion in 2021 and constituting about 70 percent of the Union’s budget. Customs duties make up around 13 percent of the Union’s revenue with around EUR 20 billion, while VAT-based contributions make up around 11 percent with around EUR 15 billion. The “plastics own resource” provides around 3 to 4 percent of the EU budget, around EUR 6 to 8 billion each year.

Compared to these resources, the new corporate own resource would not become the Union’s largest source of revenue, but it would be on par with the VAT-based resource at EUR 16 billion.

However, the GOS contribution’s interaction with the other sources of EU revenue is complex. It is essentially an exercise in double counting because GOS is largely a component of GNI. The Commission should be clear about this interaction, even if it is only a temporary measure.

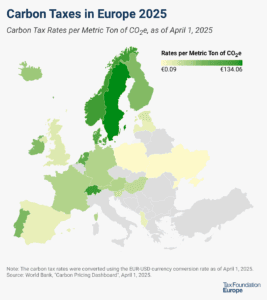

This measure complements and updates the second basket of proposed new own resources, which follows the first basket proposed in December 2022, including revenues from the emissions trading system (ETS), the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and the reallocation of residual profits from multinationals under the OECD/G20 agreement on a re-allocation of taxing rights (Pillar One).

The idea of the proposal is to have a transitory measure between now and the adoption of BEFIT, which has not yet been formally proposed, to balance the basket of own resources and diversify the revenue sources of the EU budget. EU’s budget demands have increased in recent years, especially in the context of the war in Ukraine, and as the repayment of the EU’s debt looms over. However, even without a new own resource, Member States would still be obligated to pay down the EU debt.

How Would Contributions Be Determined?

The Commission’s proposal is based on the notion of gross operating surplus, which is the national accounts term for aggregate capital income before depreciation of the capital stock. In reference to financial and non-financial corporations, GOS measures private sector corporate profits before depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. .

For European Union Member States, GOS can be derived from Eurostat national accounts data by subtracting labour compensation and taxes net subsidies on production and imports from gross value-added (GVA).

To understand the potential impact of the EU corporate own resources proposal, it is helpful to examine historical trends and hypothetical contributions from Member States.

Historical Contribution to Own Resources

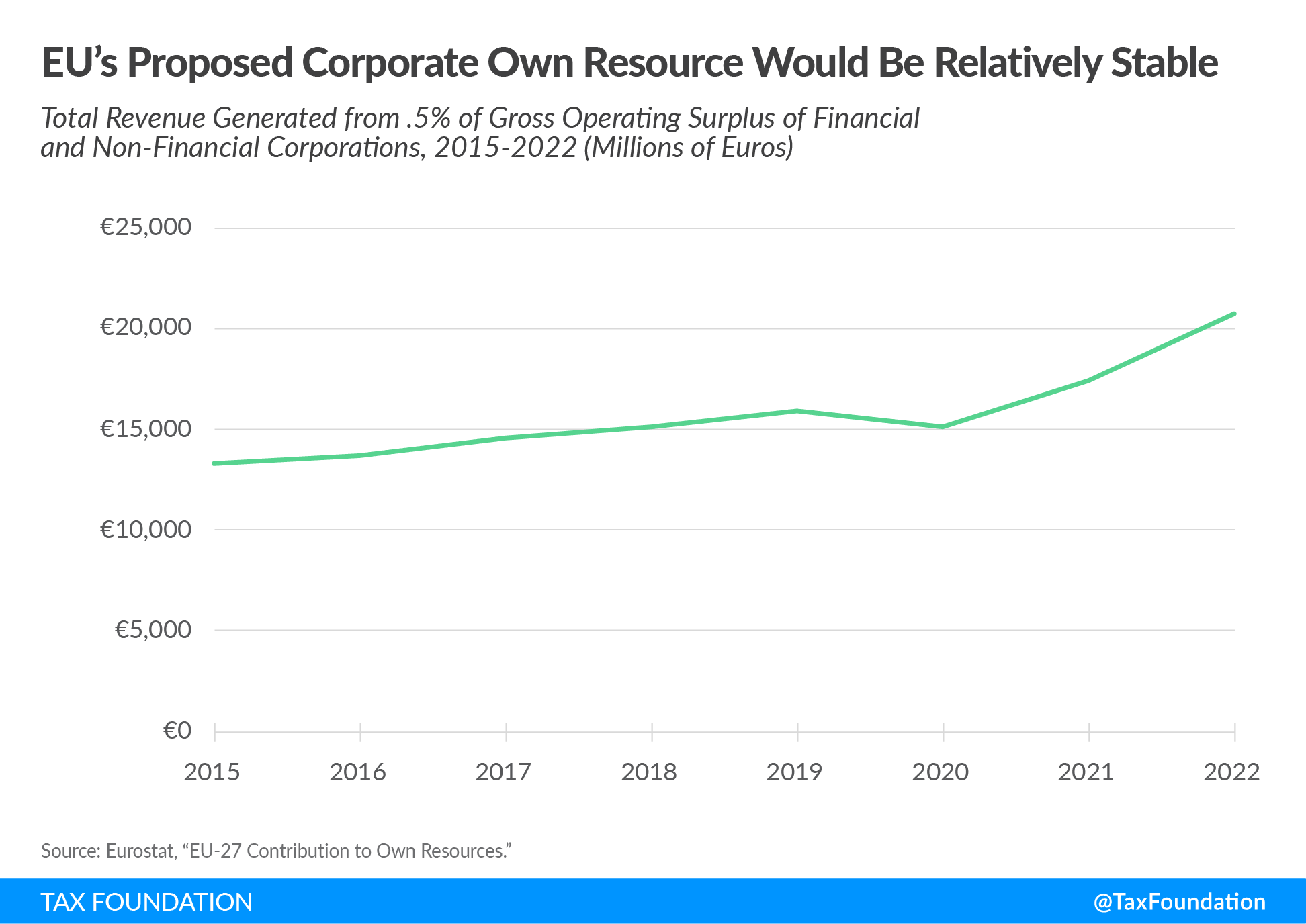

From 2015 to 2022, the total revenue that could have been raised from 0.5 percent of the gross operating surplus in the EU-27 demonstrates a relatively stable growth trend, despite a slight downturn in 2020.

What Would Member States’ Contributions Be?

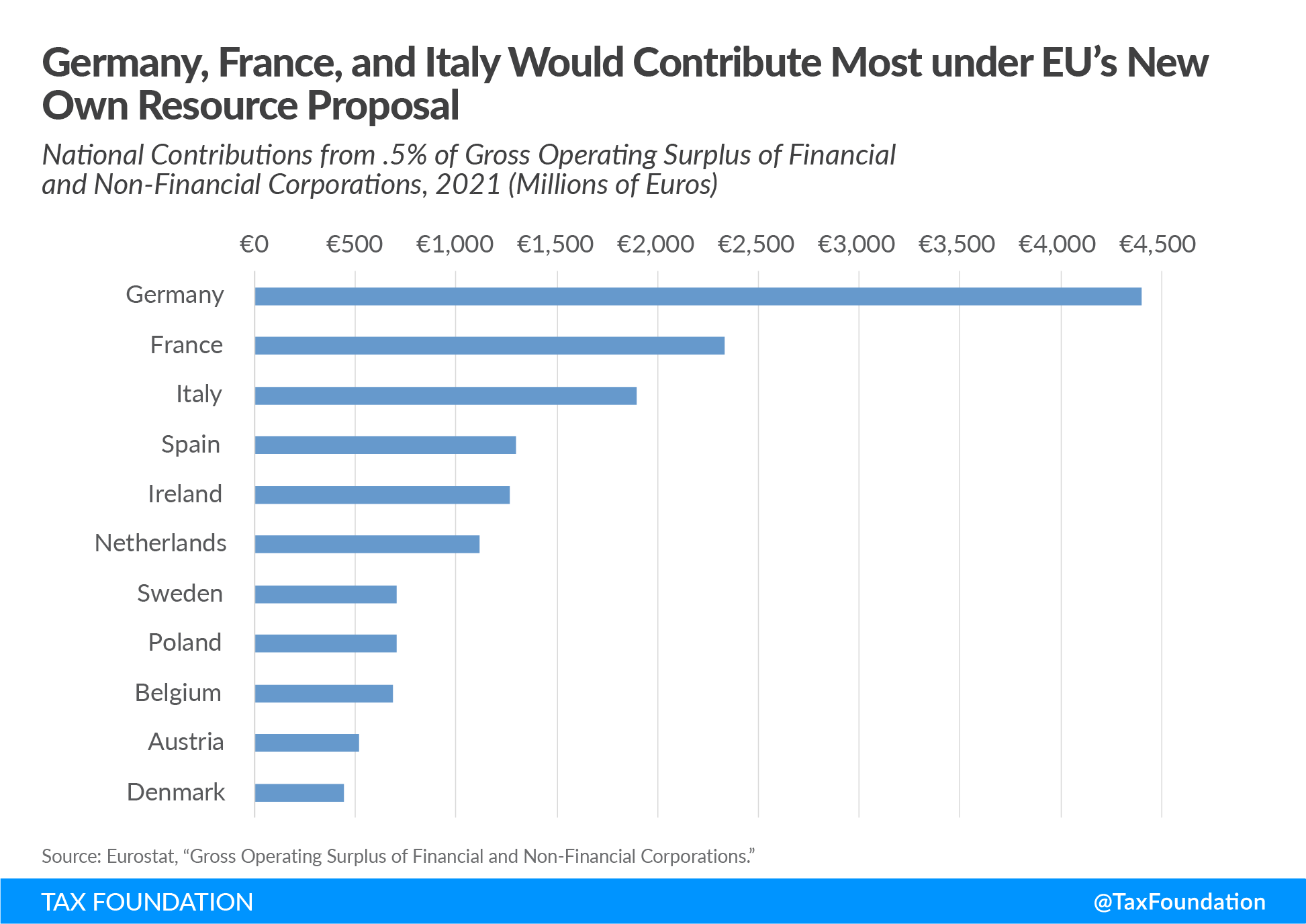

Based on calculations for 2021, we can compare individual Member States’ potential financial burden under this proposal.

Of the proposal’s expected EUR 17.44 billion in revenue, around 25 percent, or EUR 4.4 billion, would be contributed by Germany. France would contribute 2.3 billion, or 13 percent, and Italy would contribute 1.9 billion, or 11 percent. Overall, the national contributions collected by these three countries would make up half of the total expected revenue of the proposal.

Evaluating the Key Claims of the Proposal

It is true that the proposal would not directly impose any significant distortions on economic activity. Because the corporate own resource would be collected as national contributions from the Member States directly—based on their corporate gross operating surplus—and not be imposed as a direct tax on companies, it would not affect economic decision-making.

Instead, Member States are responsible for funding their respective national contributions and collecting the associated tax revenue using existing national instruments. The extent of economic distortion arising from revenue generation thus depends on the specific instruments chosen by national policymakers. To minimize such distortions, policymakers could opt for measures such as reducing national government spending or expanding the tax bases of value-added taxes (VATs).

Since the corporate gross operating surplus for EU Member States can be easily calculated using Eurostat, compliance costs associated with the measure will be relatively low.

Overall, the Commission’s proposal for a corporate own resource relies on a relatively straightforward and stable calculation. After comparing this proposal’s revenue stability and impact on economic activity with some of the other ideas for new own resources, this proposal is potentially a more favorable option—but how Member States choose to fund the contribution will determine the real economic effects. As policymakers move forward with the Own Resources Decision, it will be crucial for them to adequately recognize these dynamics.

Share this article