Among President Joe Biden’s proposals is increasing taxes on corporate income, both at the entity level and at the shareholder level. If enacted, Biden’s plan would reduce after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. for corporations and shareholders across the income distribution, reduce economic growth by over 1.5 percent, and eliminate more than half-a-million jobs.

Increasing taxes on corporate income would slow the economic recovery by limiting the investment and hiring plans of U.S. corporations.

Furthermore, it may not be widely understood that under current law, income earned by C corporations is subject to at least two layers of taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. : one at the corporate level and another at the shareholder level due to taxes on capital gains and dividends. This contrasts with pass-through firms, which do not face an entity level tax but instead pay income tax on net profit “passed through” to owners’ personal tax returns.

Ideally, taxation should be neutral with respect to a company’s legal form. Whether a firm decides to incorporate or operate as a passthrough should have more to do with business strategy than tax planning. Moreover, if income is more heavily taxed because of a firm’s legal form, this will encourage firms to change legal form and reduce or shift their investment.

Income earned by C corporations is taxed at the entity level at a federal statutory rate of 21 percent and at state statutory rates that average about 6 percent, resulting in a combined rate of 25.77 percent. After paying corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. es, the firm can either distribute its after-tax profits to shareholders through dividend payments or retain the after-tax earnings, which can raise the firm’s value. Dividends are subject to federal and state taxes, and stock appreciation is subject to federal and state capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. es when investors sell for a gain.

The top federal tax rate is 37 percent for ordinary dividends or 20 percent for qualified dividends plus 3.8 percent due to the federal net investment income tax (NIIT). In addition, states tax dividends at various top rates, resulting in an average combined federal and state 29.23 percent on qualified dividends.

Suppose that a corporation earns $100 in profit in 2020. It must pay federal and state corporate income tax of $25.77 (federal and state combined rate of 25.77%), which leaves the corporation with $74.23 in after-tax profits. If the corporation distributes those earnings as a dividend, the income is taxed again at the individual level at a top rate of 29.23 percent (federal and state combined rate on qualified dividends), resulting in $21.70 in federal and state income taxes. Thus, final after-tax income is $52.53, and the $100 in original corporate profits faces a total combined tax rate of 47.47 percent (see Table 1).

| Top Combined Tax Rate on Corporate Income Distributed as Dividends (2020) | |

|---|---|

| Corporate Income (Profit) | $100 |

| Corporate Income Tax (Combined Federal and State Statutory Rate) | -$25.77 |

| Distributed Dividends | $74.23 |

| Dividend Income Tax (Combined Federal and State Statutory Rate) | -$21.70 |

| Total After-Tax Income | $52.53 |

| Total Combined Tax Rate | 47.47% |

|

Source: Author’s calculations, based on OECD, “Corporate and Capital Income Taxes, Table II.4. Overall Statutory tax rates on dividend income,” April 2020. |

|

While 47.47 percent sounds high and is high, it is considerably lower than the 56.32 percent top combined tax rate that applied prior to passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017.

The double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. of corporate income has broad negative effects. First, the entity level tax on corporate income increases the cost of capital, leading to less investment and a lower level of output (gross domestic product, or GDP). While the corporation pays the corporate income tax, the burden of payment (incidence) is split between capital and labor. Corporations may lower wages or reduce the number of employees if after-tax returns are lower and there are fewer viable investment opportunities.

Second, taxing corporate income at the shareholder level reduces the after-tax return for investors, leading to a lower level of domestic saving and a lower level of income for Americans (gross national product, or GNP). Shareholders are not the only ones harmed by higher combined corporate taxes.

The current tax treatment of corporate income also leads to other distortions.

The tax code creates a disparity between financing investments with debt or equity. Since interest is deductible for the borrower while equity financing is not, corporations have a tax incentive to use more debt to underwrite their business ventures, causing overleverage.

Taxing gains at realization (when stock is sold) creates a lock-in effect (where investors hold assets for a long period to minimize their tax liability), since deferral reduces the effective tax rate that gains will face. The lock-in effect is inefficient in that it distorts investment away from its most profitable use to minimize tax.

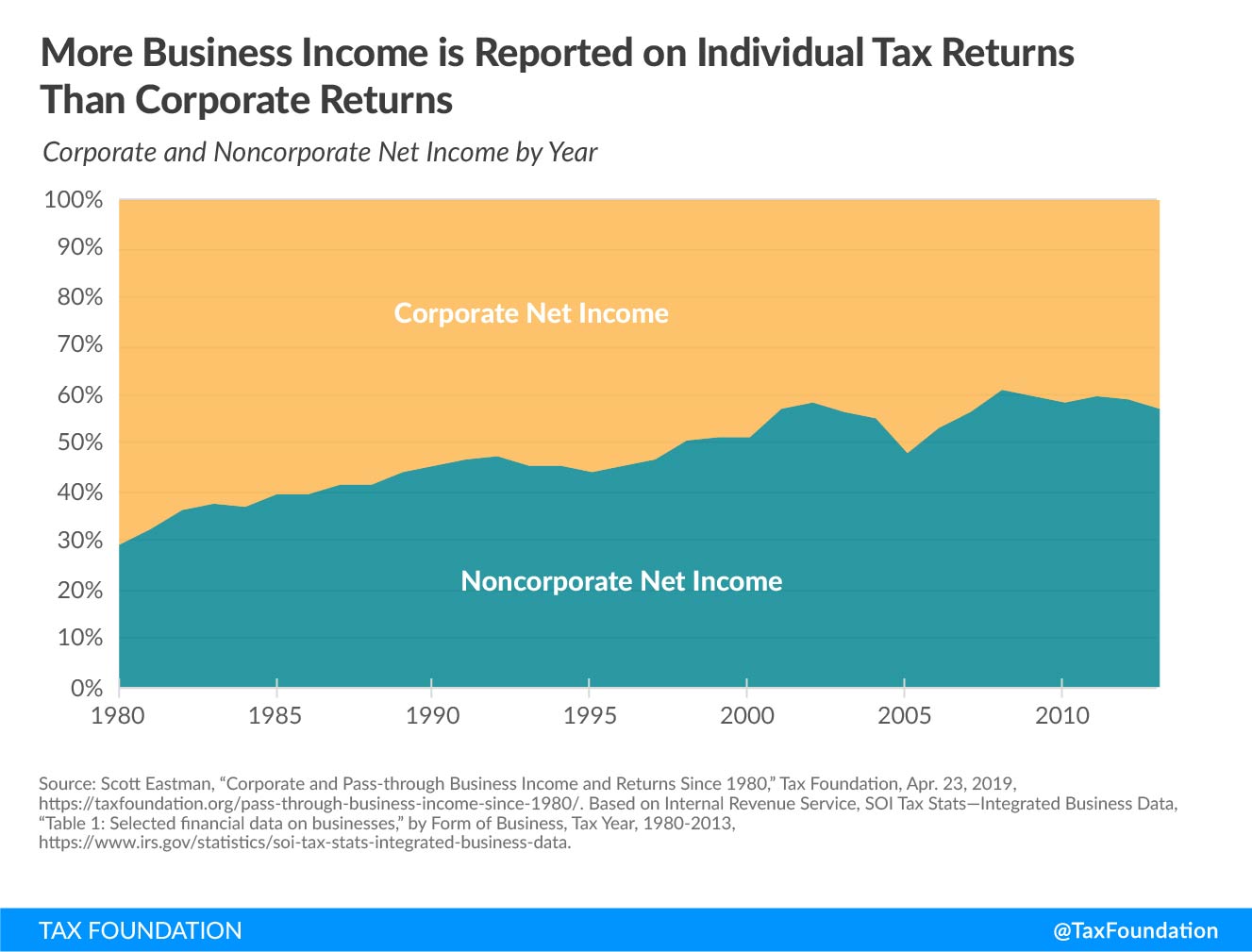

The treatment of pass-through income is in many ways more critical for us to understand than corporate income since the former constitutes the majority of business income. The number of sole proprietorships increased from about 9 million in 1980 to more than 24 million in 2013, while the number of S corporations and partnerships combined increased from 2 million to almost 8 million. In 2013, passthroughs outnumbered corporations 20:1. As of 2014, 95 percent of all businesses are organized as passthroughs. The steady growth in pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. es likely results from the availability of firms to obtain similar liability protections to corporations with fewer layers of taxation and compliance (Figure 1).

These and other distortions are why economists have proposed taxing corporate income more uniformly through corporate integration, which can be done in a variety of ways. Biden’s plan goes in the opposite direction by making worse the double taxation of corporate income.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe