What’s Next for Tax Competition?

5 min readBy:The recent agreement on a global minimum taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. and other changes to tax rules around the world have called into question the future of tax competition. And though tax competition might be changing, it isn’t going away, so the Tax Foundation’s International Tax Competitiveness Index still has lessons to offer.

In fact, the Index may become even more relevant as we enter a new phase of tax competition. The Index’s guidance on neutral, non-distortive tax policies and support for work and business investment will still be useful even in the context of a global minimum tax. While there may be less room for competition on corporate tax rates or some tax preferences, countries can still compete on overall tax system design. As countries continue to seek ways to attract business investment and workers, the global minimum tax could change the way the game is played, but not end the game itself.

Let’s start with what the new tax agreement does. First, it shifts where some large multinationals pay taxes from the location of their production to the jurisdiction of their customers. However, this portion, also known as “Pillar One,” has not been fully agreed to, and it may not be implemented. Second, it lays out a template for a minimum tax that applies to the foreign earnings of companies. Dozens of countries are ready to implement this minimum tax, also known as “Pillar Two,” in 2024 and the years following.

For tax competition and the Index, both pieces are relevant.

Over many years (including recently), academics have suggested that a global tax system that is based on where companies make their sales will likely reduce incentives for individual governments to lower their tax rates to attract profitable investments. If a country only needs the consumers (rather than the investment) to have a tax base, then it becomes less likely that countries will lower corporate tax rates to support inbound foreign direct investment. In fact, a tax system based fully on where consumption occurs would also not tax new investment.

However, Pillar One is not a pure allocation of taxable profits based on where sales are made. Instead, the reallocation only applies to a subset of profits for around the 100 largest and most profitable companies. Because of that, this part of the tax deal likely will have only limited impacts on governments that may want to reduce taxes on companies to support business expansions.

With respect to the International Tax Competitiveness Index, this part of the global deal could lead to the removal of digital services taxes. If those taxes do ultimately go away, that could improve the scores of the countries that have adopted them.

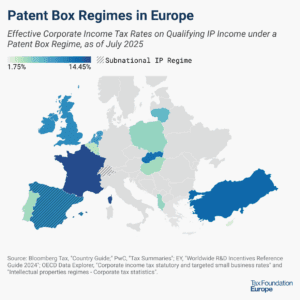

The global minimum tax also has the potential to work against tax competition and may have an impact on the Index. The minimum effective tax rate of 15 percent is above only a handful of statutory tax rates across the world, but this is not a relevant comparison. Many countries have special tax preferences for research and development and profits from intellectual property, or they provide lengthy tax holidays for new business investments. These policies regularly result in low effective tax rates on business profits.

The 15 percent global minimum effective tax rate could encourage countries to reconsider tax policies that lead to very low effective tax rates, or it might lead countries to operate multiple tax systems at once—one for domestic companies or small multinationals and a separate system for large multinationals.

As the rules have developed, policymakers have made a distinction between types of tax incentives. Tax credits that provide a reduction in effective tax rates are treated less favorably than direct subsidies or tax credits that are refundable or transferrable to another taxpayer.

In 2022, when the European Union adopted a directive on the global minimum tax, the United States adopted the InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. Reduction Act with generous tax subsidies for various environmentally friendly investments. The global minimum tax leaves room for both.

The United States also adopted a minimum tax in 2022, but that minimum tax does not align with the global minimum tax rules.

The next round of tax competition will show how tight (or loose) the minimum tax rules are, and how the complexity of the rules creates opportunities for governments to get creative in how they use fiscal policy to support business investment.

Countries will continue to compete for business investment and workers. The global minimum tax does respect business hiring and investment through targeted carveouts. Countries could change their policies that impact real investment (like rules for capital cost recovery) or the taxation of workers (like the tax burden on labor) in response to those carveouts. Reducing the tax burdens on capital investment and workers are both pro-growth, and governments could decide how to adjust other tax rules to compensate for any fiscal costs of the reforms.

Rather than simply trying to attract intellectual property assets or high-value activities, countries may see the importance of spurring domestic investment in more capital-intensive industries, including those investments that will be necessary to respond to concerns about the changing climate. Countries may also choose to become more attractive to workers who are increasingly mobile in this new era of remote working.

The World Bank and the OECD have recently published papers analyzing how the global minimum tax might change the design of countries’ tax incentives. Their recommendations are also in line with benefitting real investment and workers’ wages.

If that is what the next round of tax competition looks like, the Index will be there to capture it.

The rules of tax competition are changing, but that does not mean the contest is over. It will take time to see how different countries react, but one of the main lessons of the Index is that countries can have principled tax policies while raising sufficient revenue to finance government programs. The Index will continue to show where policymakers are adapting their rules in ways that are narrow, preferential, and distortionary rather than being broadly supportive of work and investment.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe