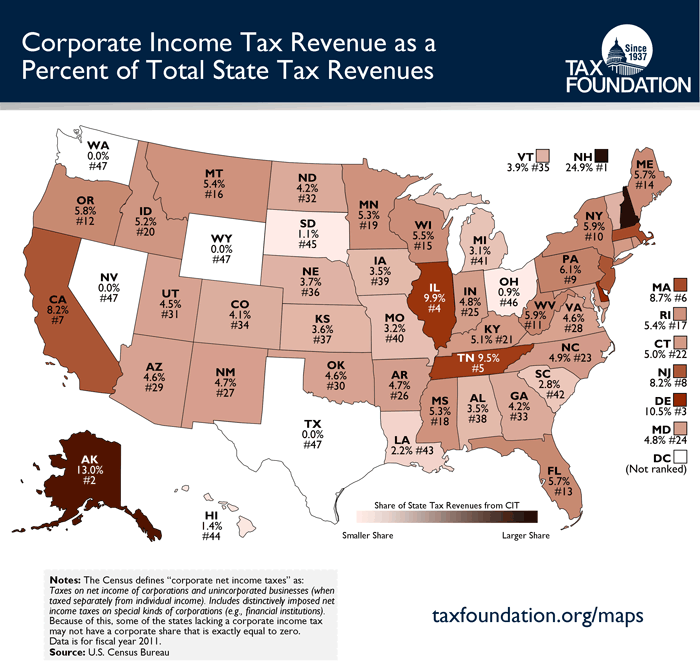

Corporate income taxes are one of the smallest sources of state government taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenue, as indicated by data from the U.S. Census Bureau. On average, only 5.4 percent of state tax revenues came from corporate income taxes in 2011 (the most recent data available). [Please note that this map discusses state tax revenues only, not state and local tax revenues together, as is outlined in our Facts and Figures booklet.]

Note that six states do not have a corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. (Nevada, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming), but three of them have a gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. (Ohio, Texas, and Washington). The Census defines “corporate net income taxes” as

Taxes on net income of corporations and unincorporated businesses (when taxed separately from individual income). Includes distinctively imposed net income taxes on special kinds of corporations (e.g., financial institutions).

Because of this, some of the states lacking a corporate income tax may not have a corporate share that is exactly equal to zero.

The top five states with the largest portion of tax revenues coming from corporate income taxes are New Hampshire (24.9 percent), Alaska (13.0 percent), Delaware (10.5 percent), Illinois (9.9 percent), and Tennessee (9.5 percent). Most of these states lack one of the major taxes and have high corporate income tax rates when compared to other states. For example, New Hampshire’s rate of 8.5 percent is 9th highest in the nation. Alaska has a progressive rate-structure with ten brackets and a top rate of 9.4 percent (5th highest).

There are a few reasons why the corporate income tax share is so low on average:

- The number of businesses organized as traditional C-corporations has decreased over time. Businesses can choose one of many forms when structuring themselves, and the number choosing to structure as a traditional corporation is shrinking. As my colleague Kyle Pomerleau pointed out in a recent report on pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. entities, "between 1980 and 2010, the total number of pass-through businesses [firms that file business taxes through the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. ] nearly tripled, from roughly 10.9 million to 30.3 million." Further, between 1980 and 2008, the number of C-corporations decreased from 2.2 million to 1.6 million. The result? There aren’t as many corporations left on which to levy the corporate income tax, thus shrinking the base.

- States hand out generous corporate tax incentive packages to entice businesses to move to (or remain in) their states. Business tax incentives are popular among state lawmakers. These include things such as jobs credits and investment credits. These lower the tax liability for certain businesses and industries that are engaging in activities that lawmakers deem desirable at the time. In addition to the fact that they are distortionary and non-neutral, incentives such as these carve away at the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , reducing tax revenue.

- States further reduce corporate tax bills by fiddling with income apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders.

formulas, reducing the in-state taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income.

of corporations within their borders. Income apportionment "formulas are used by states to determine what percentage of a corporation's profits are taxed. Generally, three categories are used: property, payroll, and sales." But an increasing number of states have started using sales-only apportionment or have even weighted sales more heavily than other factors. Changing apportionment formulas is a way to reduce the amount of taxable income for certain types of companies within a state without changing tax rates or tax bases, two things that can be politically difficult to do. According to Professor David Brunori (in State Tax Policy: A Political Perspective),

Using a double-weighted or single-sales factor usually lowers tax burdens for

corporations that have substantial operations within a state (as measured by

payroll and property) but sell most of their goods and services out of state.

Indeed, scholars have found that moving to a single-sales factor apportionment

formula decreases corporate income tax revenue by as much as 10 percent

(Edmiston 2002).

All of these practices have carved away at the state corporate income tax base, making it a small source of state tax revenue when compared to other types of state taxes.

Share this article