On January 4, Indiana legislative leaders unveiled a plan to raise fuel taxes by 10 cents per gallon, increase the vehicle registration fee by $15 per year, and create a $150 per year fee on electric vehicles. All told, the plan would raise $300 million per year, costing the average Hoosier about $5 per month.

Road funding is a hot topic across the country. Over twenty states have raised their gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. in the last three years, with seven states seeing increases this year already and a dozen more actively considering changes. Why? One big reason is that most gas taxes are fixed amounts that don’t adjust for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. , so the revenue collected stays the same as expenses even for maintaining the status quo grow each year. Other reasons include better gas mileage, more hybrid and electric vehicles, and a shift of population from the suburbs back to the cities, which have all led to an unprecedented drop in vehicle mileage growth compared to the historical average.

All this puts pressure on federal and state transportation programs that pay their expenses out of user-related taxes and fees like state gas and diesel taxes, vehicle fees, and tolls. We’ll be putting out a report soon on this, but road- and vehicle-based taxes and fees imposed by state and local governments cover only 52 percent of state and local road spending. Some of the gap is covered by federal transfers for transportation but states have to dip into general taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenues that compete with other priorities. Even the federal dollars are problematic, since the federal gasoline tax faces a similar insufficiency crisis and general tax revenue has on several occasions bailed out the federal transportation trust funds.

Indiana is no exception to these larger trends. The state and its local governments aren’t spendthrifts; they spend $2.5 billion per year on roads, or about $381 per Hoosier, the sixth lowest level in the country. Only 43 percent of this cost is currently covered from user-related taxes and fees like fuel taxes and the vehicle license tax. A transportation task force last year estimated a $1 billion-a-year infrastructure wish list, and recommended that legislators increase funding by increasing user taxes and adjusting them automatically for inflation, and that INDOT (Indiana Department of Transportation) adopt new metrics and models to ensure maximum benefits over costs from projects it undertakes. The legislative proposal is based on these recommendations.

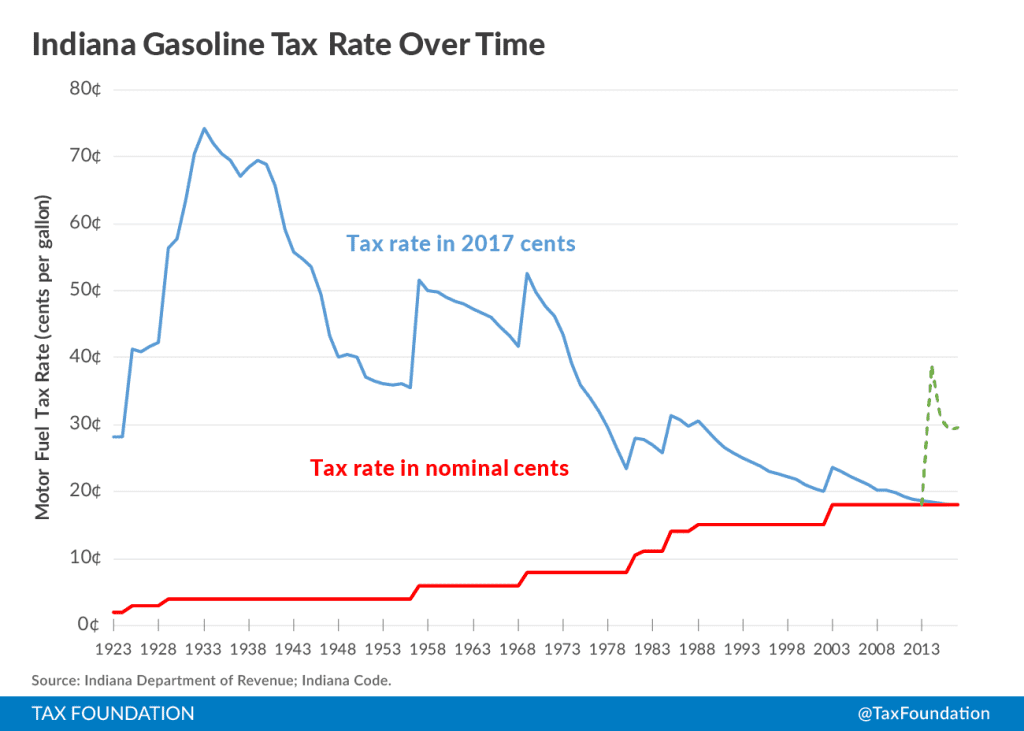

Indiana’s gas tax is currently 18 cents per gallon; the proposal would raise it to 28 cents per gallon. Even with the increase, it would be on the historical low-end for the state, as the chart below shows. Until the 1970s, the Indiana gas tax was usually set at the modern-day equivalent of 40 cents per gallon or more. (The green dashed spike in 2014 is the swap that repealed the 7 percent sales tax on gasoline and replaced it with a gasoline use tax of 7 percent of the price; it didn’t actually change pump prices.)

The lion’s share of transportation funding should come from user fees (amounts, such as tolls, a user pays directly for a service the user receives), and user taxes (amounts a user pays, based on usage, for transportation, such as fuel and motor vehicle license taxes). When road funding comes from a mix of tolls and gasoline taxes, the people who use the roads bear a sizable portion of the cost. By contrast, funding transportation out of general revenue makes roads “free,” and consequently, overused or congested—often the precise problem transportation spending programs are meant to solve.

Increasing and inflation-indexing gasoline taxes may not be politically popular despite the highly popular nature of transportation facilities and services. Given that transportation spending exists, states should aim to fund as much of it as possible from user fees and user taxes. Subsidizing road spending from general revenues creates pressure to increase income or sales taxes, which can be unfair to non-users and undermine economic growth for the state as a whole.

Share this article