Key Findings

- Taxpayers who itemize deductions on their federal income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. are permitted to deduct certain taxes paid to state and local governments from their gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” for federal income tax liability purposes.

- State and local tax deductibility would be repealed under the House Republican Blueprint, and capped—along with other itemized deductions—under the campaign plan put forward by President Donald Trump.

- The state and local tax deductionA tax deduction is a provision that reduces taxable income. A standard deduction is a single deduction at a fixed amount. Itemized deductions are popular among higher-income taxpayers who often have significant deductible expenses, such as state and local taxes paid, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions. disproportionately benefits high-income taxpayers, with more than 88 percent of the benefit flowing to those with incomes in excess of $100,000.

- The deduction favors high-income, high-tax states like California and New York, which together receive nearly one-third of the deduction’s total value nationwide. Six states—California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Texas, and Pennsylvania—claim more than half of the value of the deduction.

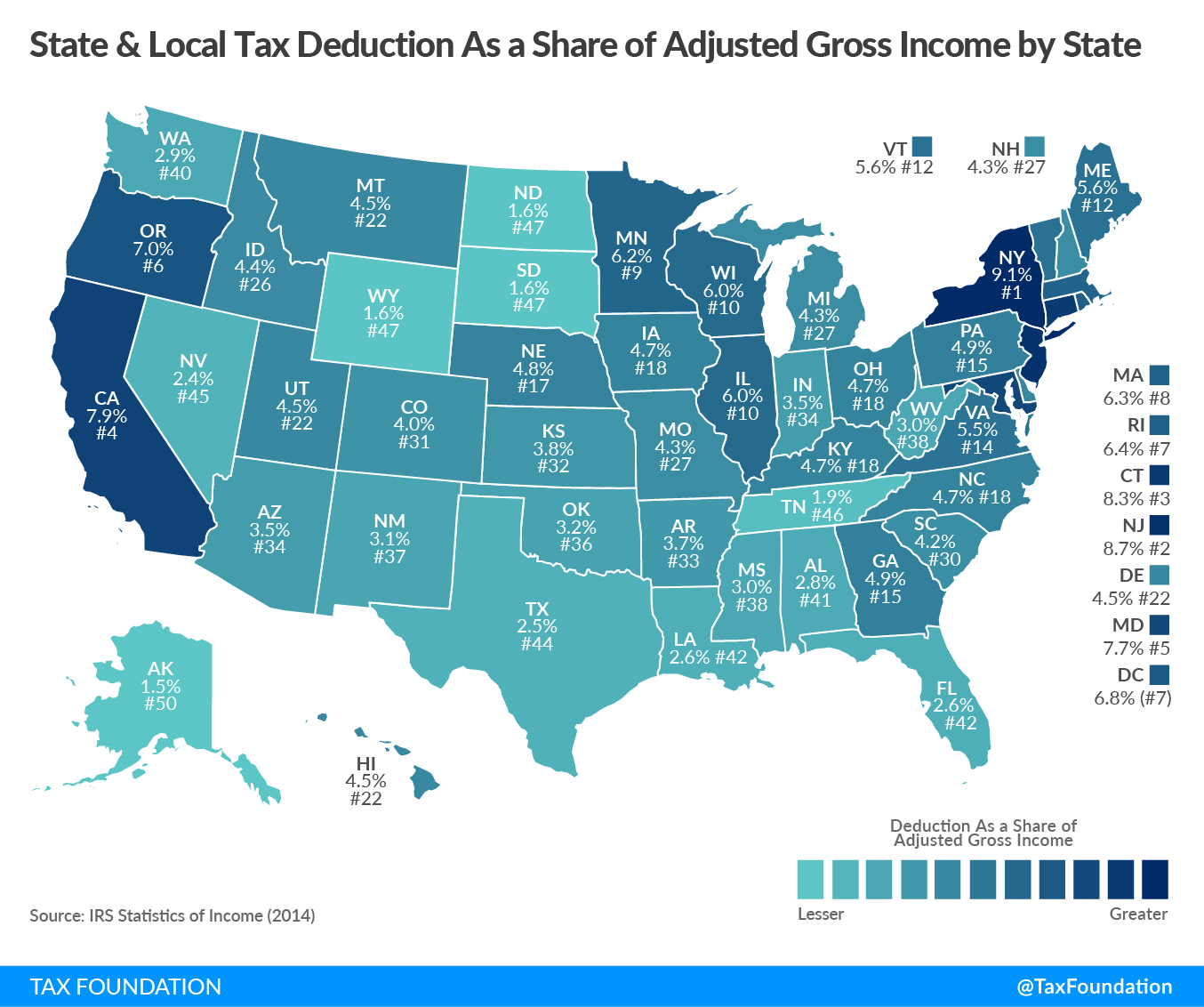

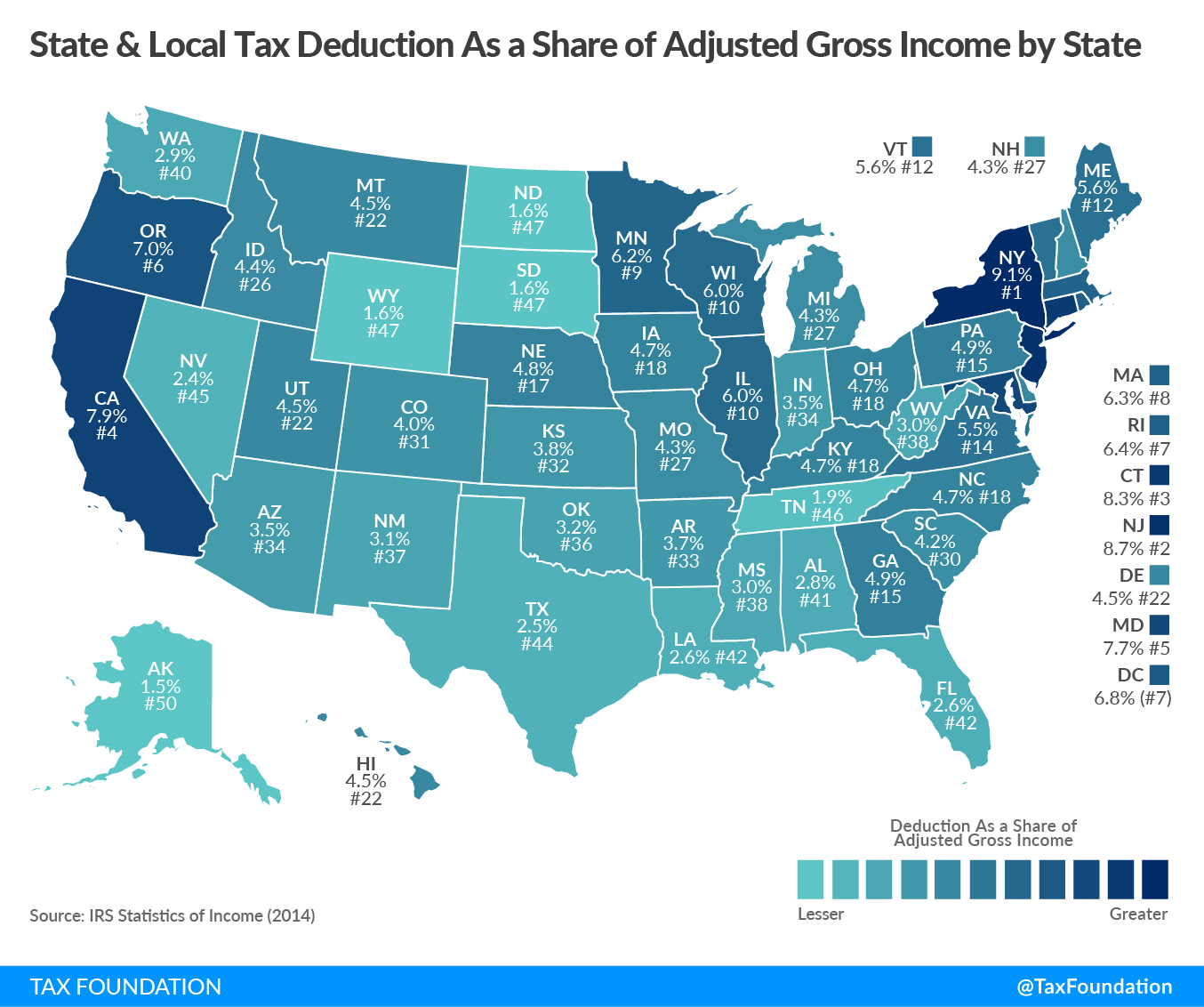

- The state and local tax deduction in New York and California represents 9.1 and 7.9 percent of adjusted gross income respectively, compared to a median of 4.5 percent.

- The deduction reduces the cost of state and local government expenditures, particularly in high-income areas, with lower-income states and regions subsidizing higher-income, higher-tax jurisdictions.

Introduction

For Ronald Reagan, it was “the most sacred of cows.”[1] To Donald Regan, his Secretary of the Treasury, it was a “dragon” to be slayed.[2] Whatever its taxonomy, the state and local tax deduction has proved resilient, warding off foes for decades. It has withstood the accusation that it is regressive, rewarding high-income taxpayers. It has persevered despite being labeled a subsidy of wealthy, high-tax states funded by the rest of the country. It has endured economists’ suspicion that it distorts state and local government expenditures. Thanks to the tenacious support it enjoys in some quarters, it has survived parries from the left and from the right. Again imperiled by the House Republican tax reform plan, which would eliminate all itemized deductionItemized deductions allow individuals to subtract designated expenses from their taxable income and can be claimed in lieu of the standard deduction. Itemized deductions include those for state and local taxes, charitable contributions, and mortgage interest. An estimated 13.7 percent of filers itemized in 2019, most being high-income taxpayers. s save those for mortgage interest and charitable contributions, its long-heralded demise might actually be in sight.

Applicability of the Deduction

Under current law, taxpayers who itemize are permitted to deduct certain nonbusiness tax payments to state and local governments from their taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . An individual may choose to deduct either state individual income taxes or general sales taxes, but not both, and may also deduct any real or personal property taxes.[3] Most filers elect to deduct their state and local income taxes rather than sales taxes, because income tax payments tend to be larger, but those who reside in states which forego an income tax, or who have uncommonly high consumption expenditures in a given year, may opt to deduct sales taxes instead. The sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. deduction may be taken either by documenting actual expenses or through the use of an optional sales tax table based on personal income.[4]

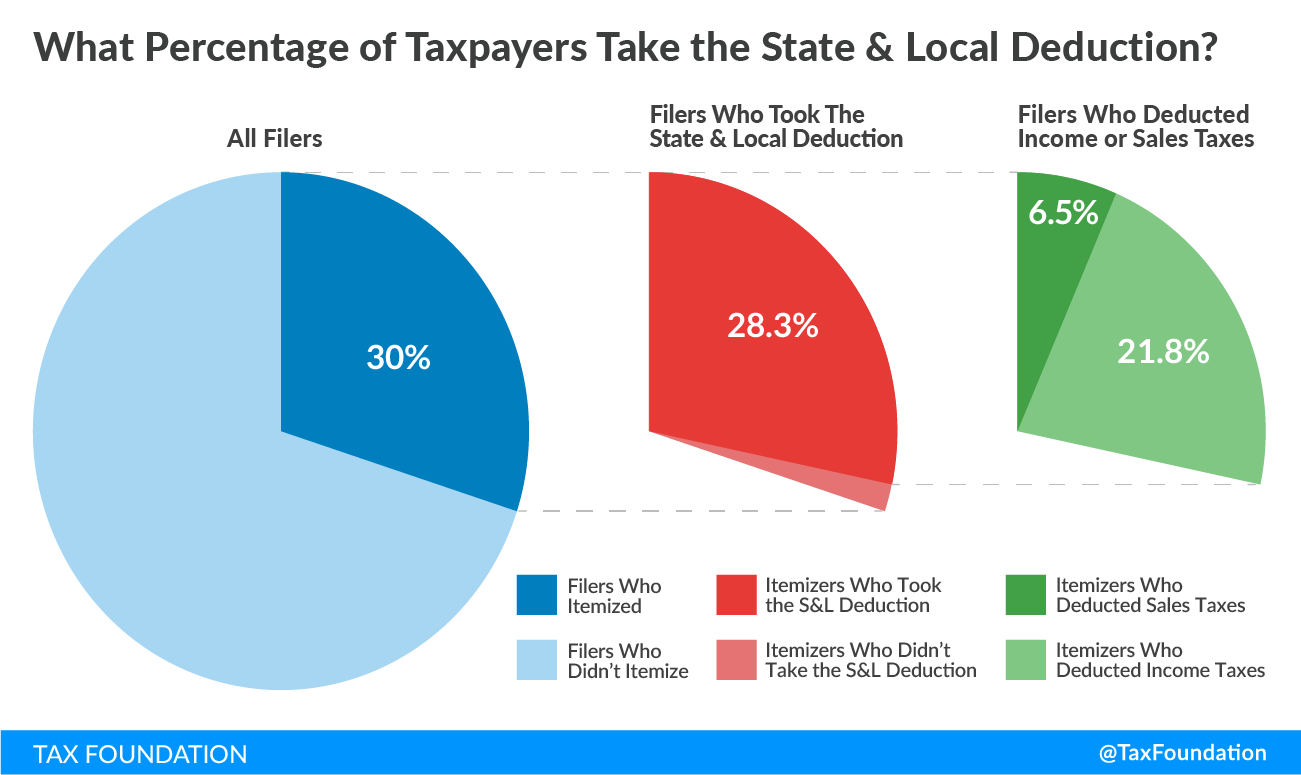

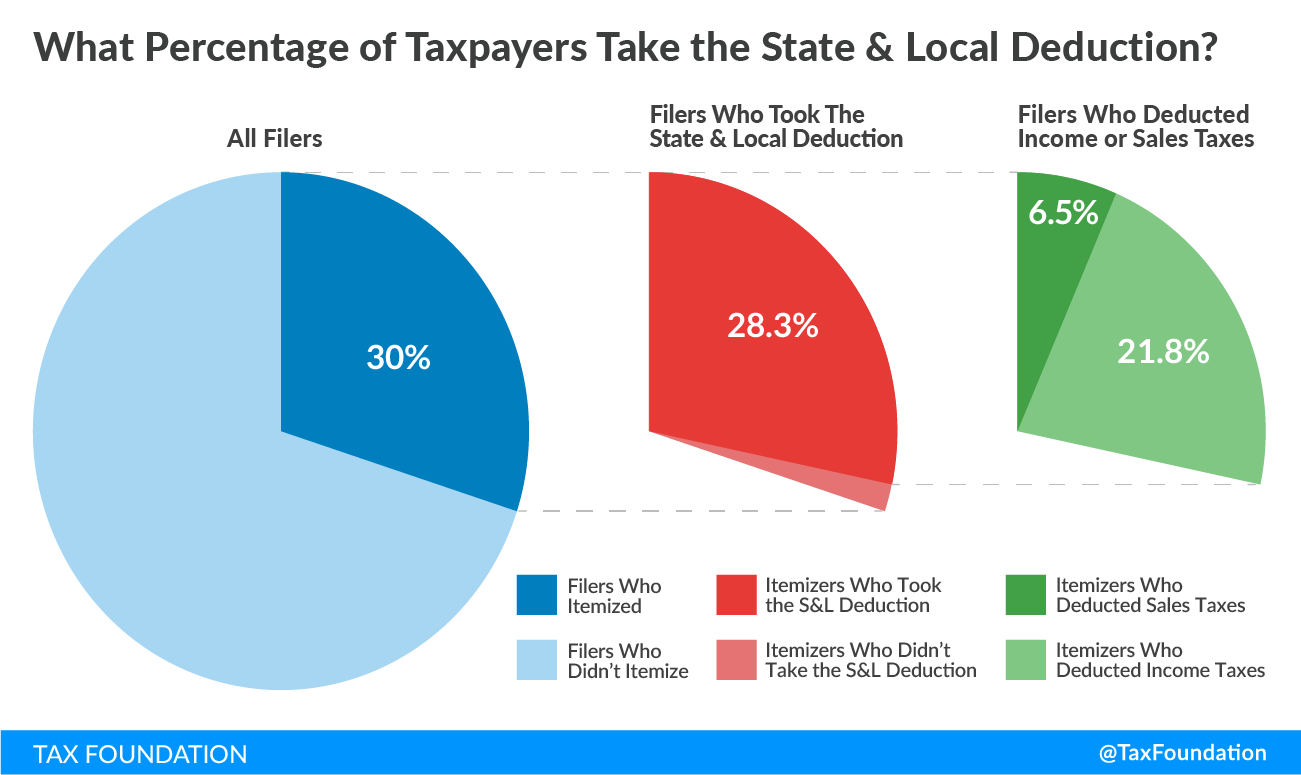

In tax year 2014, more than 95 percent of all itemizers, and 28 percent of all federal income tax filers, took a deduction for state and local taxes. Roughly 21.8 percent of filers deducted income taxes, while 6.5 percent elected to deduct sales taxes instead. Most itemizers are homeowners, so 25.1 percent of filers (representing 84.7 percent of itemizers) also took the deduction for real property taxes.[5] Taken together, deductions for state and local taxes represent the sixth largest individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. expenditure, estimated to be worth more than $100 billion per year by fiscal year 2018[6] even though most filers do not itemize.[7]

The value of the deduction is lessened for some payers by the Pease limitation, which reduces itemized deductions by 3 percent of the amount that a taxpayer’s adjusted gross income exceeds an indexed threshold,[8] and by the alternative minimum tax. The House Republican tax plan, like several before it, would repeal the deductibility of state and local taxes outright (along with most other itemized deductions) in favor of significantly lower rates.[9]

History of State and Local Tax Deductibility

The deductibility of state and local taxes is older than the current federal income tax itself. The provision has its origin in the nation’s first effort at income taxation (eventually found unconstitutional) under the Civil War-financing Revenue Act of 1862, and was carried over into the Revenue Act of 1913, the post-Sixteenth Amendment legislation creating the modern individual income tax. The rationale for the original provision only comes down to us in fragments, though a fear that high levels of federal taxation might “absorb all [the states’] taxable resources,” a concern first addressed in the Federalist Papers, appears to have held sway.[10] Lawmakers sought a bulwark against the possibility that “all the resources of taxation might by degrees become the subjects of federal monopoly, to the entire exclusion and destruction of state governments,”[11] and found it in a federal deduction for state and local taxes.

This caution would appear prescient as top marginal rates soared from 7 percent in 1913 to 77 percent by 1918 as American doughboys took to European fields, and in 1944, when the top rate skyrocketed to 94 percent at the height of the Second World War. Even in the postwar era, the top marginal rate would remain at 91 or 92 percent every year from 1951 until 1964, when it declined with the implementation of the Kennedy tax cuts.[12] During this era, the state and local tax deduction prevented combined federal, state, and local income tax rates from exceeding 100 percent.[13]

In time, however, the prudence of the provision would be called into question. Neglecting some modest tinkering—the exclusion of license fees and excise taxes on alcohol and cigarettes in 1964, and later the exclusion of motor fuel excise taxes—the state and local tax deduction went largely unchallenged until the U.S. Department of the Treasury, under the direction of Secretary William E. Simon, issued Blueprints for Basic Tax Reform in the waning days of the Ford administration. The report, issued in January 1977, recommended the retention of state and local income tax deductibility while jettisoning the deduction for sales and property taxes.[14]

In 1983, Senator Bill Bradley and Congressman Dick Gephardt teamed up on a Democratic tax reform proposal that sought to proscribe the deduction, limiting it to income and real property taxes. A competing Republican plan introduced by Congressman Jack Kemp and Senator Bob Kasten would have retained it exclusively for real property taxes. Then, in 1984, at the behest of President Ronald Reagan and with Secretary Donald Regan at the helm, the Treasury unveiled a comprehensive tax reform proposal (retrospectively known as Treasury I) which incorporated the complete elimination of state and local tax deductibility.[15] After decades of quiet existence, the deduction was suddenly vulnerable, and the stage was set for it to assume a central role in the debate surrounding the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

“We were slaying a lot of dragons,” Secretary Regan would later say, reminiscing about the heady days when, working in secret, a small cadre of Treasury staffers slashed through the tax code to develop a comprehensive tax reform proposal that could be championed by President Reagan.[16] Dragons, however, are not easily slain, and this one had powerful defenders.

A high-income and high-tax state, New York—and particularly New York’s wealthy elite—benefited mightily from the deduction, which one congressman from the state termed “a matter of survival.” Governor Mario Cuomo, Senator Alfonse D’Amato, and a powerful coalition studded with luminaries the likes of David Rockefeller (chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank), James Robinson III (chairman of American Express), and Laurence Tisch (chairman of Loews Corporation), joined by public sector unions and the Conference of Mayors, went to war. In time, proponents of state and local tax deductibility would forge alliances with other interests threatened by tax reform, and their advocacy very nearly derailed the entire tax reform agenda.[17]

In the end, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 did nothing more than withdraw the general sales tax deduction, which was later restored in part.[18] In 2005, an advisory panel convened by President George W. Bush declared that eliminating the deduction would offer a “cleaner and broader tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. ” and a more equitable tax code, though nothing came of it.[19] But if the dragon had not been felled in the 1986 tax reform effort, neither had its foes. Today, the deductibility of state and local taxes again finds itself on the chopping block, recommended for elimination along with most other itemized deductions by the House Republican tax reform “Blueprint” championed by Speaker Paul Ryan and House Ways and Means CommitteeThe Committee on Ways and Means, more commonly referred to as the House Ways and Means Committee, is one of 29 U.S. House of Representative committees and is the chief tax-writing committee in the U.S. The House Ways and Means Committee has jurisdiction over all bills relating to taxes and other revenue generation, as well as spending programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance, among others. Chairman Kevin Brady. So too, the old arguments reemerge.

Four decades after the Treasury Department first floated the curtailment of deductibility, it is again necessary to consider the intended purposes of the state and local tax deduction and the arguments advanced for and against its continuation.

Opponents of the state and local tax deduction point out that it is regressive in that it is largely claimed by wealthier taxpayers, that it subsidizes higher taxes and potentially wasteful state and local spending, that it involves a transfer from lower-income to higher-income states, that it may encourage self-segregation by income groups, and that it favors public over private provision of certain services. Proponents counter that the deduction better aligns taxable income with ability to pay. They also argue that subsidization of local government expenditures offsets a tendency toward providing less than the optimal amount of government services, as determined by local taxpayers, due to what are known as spillover effects. Some local expenditures chiefly or exclusively benefit local residents, while others benefit residents and nonresidents alike. If residents are less willing to pay for government services that benefit nonresidents as well, they may settle on a lower level of service provision than they would prefer absent the spillover. Each of these arguments will be considered in turn.

Benefits for High-Income Taxpayers

The lion’s share of state and local tax deductions are claimed by upper-income earners. Only 30 percent of all federal income tax filers itemized rather than claiming the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. in tax year 2014. Of these, over three-quarters reported adjusted gross income (AGI) above $50,000, even though taxpayers with AGIs above $50,000 represent a mere 38 percent of all filers.[20] According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, more than 88 percent of the benefit of state and local tax deductions accrued to those with incomes in excess of $100,000 in 2014, while only 1 percent flowed to taxpayers with incomes below $50,000.[21] In 1984, a Treasury report went so far as to disparage the state and local tax deduction’s “distributionally perverse pattern of subsidies.”[22]

Figure 1.

A similar distribution is evident when comparing the value of the state and local tax deduction as a percentage of AGI for taxpayers in different income strata. Taxpayers with AGIs between $25,000 and $50,000 claim, in aggregate, state and local tax deductions worth 2.1 percent of AGI, whereas taxpayers with incomes above $500,000 claim deductions worth nearly 7.1 percent of AGI.[23] The elimination of deductibility would reduce the cash income of the top decile of income earners by 1.3 percent, but the reduction would be less than 0.1 percent for each of the bottom five deciles.[24]

|

Adjusted Gross Income |

S+L Deduction Value as % of AGI |

Percentage of Filers Itemizing |

|---|---|---|

|

$0 – $24,999 |

2.06% |

5.53% |

|

$25,000 – $49,999 |

2.10% |

19.77% |

|

$50,000 – $99,999 |

3.95% |

45.63% |

|

$100,000 – $499,999 |

6.55% |

80.55% |

|

$500,000 + |

7.07% |

92.16% |

| Source: IRS Statistics of Income (2014) | ||

Proponents sometimes posit that the elimination of deductibility would particularly disadvantage wealthy people who live in low-income communities, which could incentivize high-income earners to self-segregate in wealthier neighborhoods.[25] Studies, however, suggest that this effect would be quite modest, if it exists at all,[26] and that in many cases, the effect may run in the opposite direction. High-income earners who congregate in a single community, for instance, may support locally-funded amenities like golf courses and tennis courts, or more stately government buildings and costly public infrastructure—expenditures less likely to earn the support of high earners in mixed-income communities—while exporting some of the resulting tax burden to others.[27]

Subsidization of High-Income, High-Tax States

Just as the state and local tax deduction disproportionately favors wealthier taxpayers, it also benefits states which combine high incomes and high-tax environments. Reliance on the deduction varies widely: the average value of the state and local deduction as a percentage of AGI in the ten states with the highest reliance on the deductions is 6.09 percent, whereas it is only 3.81 percent in the bottom ten states. In New York, the deduction is worth 9.1 percent of AGI; the median across all states is just under 4.5 percent. More staggering, though, is the fact that just six states—California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Texas, and Pennsylvania—claim more than half of the value of all state and local tax deductions nationwide, with California alone responsible for 19.6 percent of the national tax expenditureTax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. cost.[28]

|

State |

AGI Per Filer |

% of Itemizers |

Deduction as % of AGI |

State Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alabama |

$52,741 |

26.0% |

2.8% |

0.6% |

|

Alaska |

$67,212 |

22.2% |

1.5% |

0.1% |

|

Arizona |

$56,903 |

28.3% |

3.5% |

1.1% |

|

Arkansas |

$53,186 |

22.7% |

3.7% |

0.5% |

|

California |

$73,938 |

33.9% |

7.9% |

19.6% |

|

Colorado |

$70,342 |

32.6% |

4.0% |

1.4% |

|

Connecticut |

$93,806 |

41.2% |

8.3% |

2.6% |

|

Delaware |

$61,998 |

32.0% |

4.5% |

0.2% |

|

Florida |

$60,676 |

22.9% |

2.6% |

2.8% |

|

Georgia |

$57,899 |

32.7% |

4.9% |

2.4% |

|

Hawaii |

$58,209 |

29.2% |

4.5% |

0.3% |

|

Idaho |

$52,703 |

27.9% |

4.4% |

0.3% |

|

Illinois |

$69,186 |

32.4% |

6.0% |

5.0% |

|

Indiana |

$54,125 |

23.1% |

3.5% |

1.1% |

|

Iowa |

$59,559 |

29.2% |

4.7% |

0.8% |

|

Kansas |

$62,299 |

25.7% |

3.8% |

0.6% |

|

Kentucky |

$51,977 |

26.0% |

4.7% |

0.9% |

|

Louisiana |

$57,560 |

22.8% |

2.6% |

0.6% |

|

Maine |

$53,519 |

27.6% |

5.6% |

0.4% |

|

Maryland |

$72,746 |

45.2% |

7.7% |

3.2% |

|

Massachusetts |

$85,408 |

36.8% |

6.3% |

3.5% |

|

Michigan |

$56,937 |

26.5% |

4.3% |

2.2% |

|

Minnesota |

$68,649 |

35.0% |

6.2% |

2.2% |

|

Mississippi |

$46,639 |

22.9% |

3.0% |

0.3% |

|

Missouri |

$56,634 |

26.1% |

4.3% |

1.3% |

|

Montana |

$55,240 |

28.2% |

4.5% |

0.2% |

|

Nebraska |

$61,711 |

27.8% |

4.8% |

0.5% |

|

Nevada |

$58,745 |

24.6% |

2.4% |

0.4% |

|

New Hampshire |

$69,498 |

31.5% |

4.3% |

0.4% |

|

New Jersey |

$81,344 |

41.1% |

8.7% |

5.9% |

|

New Mexico |

$50,743 |

22.7% |

3.1% |

0.3% |

|

New York |

$79,268 |

34.2% |

9.1% |

13.3% |

|

North Carolina |

$56,385 |

29.1% |

4.7% |

2.2% |

|

North Dakota |

$73,499 |

17.7% |

1.6% |

0.1% |

|

Ohio |

$56,322 |

26.5% |

4.7% |

2.9% |

|

Oklahoma |

$59,450 |

24.0% |

3.2% |

0.6% |

|

Oregon |

$59,845 |

36.0% |

7.0% |

1.5% |

|

Pennsylvania |

$63,037 |

28.8% |

4.9% |

3.7% |

|

Rhode Island |

$62,296 |

32.9% |

6.4% |

0.4% |

|

South Carolina |

$52,434 |

27.0% |

4.2% |

0.9% |

|

South Dakota |

$60,690 |

17.3% |

1.6% |

0.1% |

|

Tennessee |

$54,997 |

20.0% |

1.9% |

0.6% |

|

Texas |

$67,253 |

23.0% |

2.5% |

3.9% |

|

Utah |

$60,792 |

35.4% |

4.5% |

0.7% |

|

Vermont |

$57,573 |

27.5% |

5.6% |

0.2% |

|

Virginia |

$72,151 |

37.2% |

5.5% |

3.0% |

|

Washington |

$73,010 |

30.4% |

2.9% |

1.4% |

|

West Virginia |

$50,401 |

17.1% |

3.0% |

0.2% |

|

Wisconsin |

$59,596 |

31.6% |

6.0% |

1.9% |

|

Wyoming |

$77,370 |

21.9% |

1.6% |

0.1% |

|

District of Columbia |

$88,430 |

39.4% |

6.8% |

0.4% |

|

Source: IRS Statistics of Income (2014) |

||||

To some degree, this is a function of population. Any tax provision, no matter how neutral its application, will flow more to states with higher populations. The state and local tax deduction, however, expressly favors higher-income earners and state and local governments which impose above-average tax burdens. The deduction’s effect is for lower- and middle-income taxpayers to subsidize more generous spending in wealthier states like California, New York, and New Jersey, reducing the felt cost of higher taxes in those states. As the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center has observed, state and local governments “are able to raise revenues from deductible state and local taxes that exceed the net cost to taxpayers of paying those taxes, in effect allowing those jurisdictions to export a portion of their tax burden to the rest of the nation.”[29]

To the extent that the more generous spending is financed through progressive taxation at the state level—which might be imposed at higher rates and on more progressive schedules than would have been viable in the absence of the deduction—some of the regressive effect of the deduction at the federal level may be offset at the state level.[30] This is, however, an inefficient and convoluted approach to promoting state tax progressivity, and whatever greater progressivity may exist in a high-income, high-tax state is countered by a federal transfer away from residents of lower-income, lower-tax states. Advocates of progressive taxation typically prefer progressivity at the federal level to progressivity at the state level, as “higher-income taxpayers can avoid progressive state and local taxes either by shifting income or physically moving to a lower-tax state.”[31] The state and local tax deduction flips this preference on its head, sacrificing progressivity at the federal level in hopes of inducing more progressive state tax structures.

Figure 2.

Effect on State and Local Government Finances

Deductibility of state and local taxes increases state and local government expenditures by reducing the cost of that spending, but estimates differ on the magnitude of the effect. During the 1986 tax reform debate, the Congressional Research Service estimated that the deduction increased state and local spending by as much as 20.5 percent, while the now-defunct U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Affairs concluded that the increase was on the order of 7 percent[32] and the National League of Cities arrived at an estimate of only 2 percent.[33] Other studies have found little evidence of any significant effect on state and local government expenditure levels.[34] Furthermore, any reductions in local expenditures “would appear to be concentrated in high income communities where most itemizers now live,” according to one such study.[35]

By decreasing the cost of state and local government spending, the federal government provides a subsidy for such expenditures. Because not all forms of state and local revenue are deductible, moreover, the deduction’s availability can promote greater reliance on deductible income and property taxes to the disadvantage of other possible sources of revenue, including user fees, which might otherwise be favored.[36] Using federal tax revenue to subsidize state and local governments—and particularly higher-income taxpayers—has critics on both the left and right, with the chief argument advanced in favor of the status quo predicated on the postulate that local government spending, in particular, is suboptimal.

All levels of government must strike a balance between demand for government-provided services and the desire to keep taxes and spending in check, and the democratically chosen balance will vary from place to place. The residents of some localities are willing to accept higher levels of taxation in exchange for greater government service provision; others prefer a smaller government which necessitates lower rates of taxation. Taxpayers may be supportive of increased levels of spending if part of the cost is borne by others; conversely, they may reduce expenditures if they believe that some of the benefit of that spending will be conferred on others. Federal subsidies thus place a thumb on the scale, distorting local decision-making.[37]

Some municipal services are inherently excludable; only residents, for instance, stand to benefit from municipal trash collection. Other amenities, however, like city parks, public parking, bike trails, community centers, and municipal athletic facilities, are utilized both by residents (who pay local taxes) and nonresidents (who do not) alike. This “spillover” theoretically reduces the amount that local residents are willing to pay in taxes for certain services to a level below what they would favor if the benefits accrued only to them.[38] A federal subsidy, regressive though it may be, might then be rationalized as a way to restore expenditure decisions to equilibrium rather than artificially inflating demand.

Several objections to this model quickly emerge. As the economist Helen Ladd argues, “Positive spillovers from public sector spending are more likely in low-income or heterogeneous cities than in higher-income communities where itemizing is more common,”[39] which is one reason why, under the current regime of tax deductibility, high-income individuals may find it even more advantageous to live together in the same communities. Moreover, the deduction is a blunt instrument, applying no matter what the possible spillover effect of an expenditure is, and without regard to the mix of services that exist in a community.[40] Many public expenditures have little or no spillover, yet they receive the same subsidy as those easily enjoyed by nonresidents. Specifically, it is highly unlikely that much spillover exists from high-income to low-income communities, yet it is high-income areas and taxpayers who benefit disproportionately from the deduction.

The argument particularly suffers if local government revenues hew closely to the benefit test, where tax (and fee) liability closely tracks benefits received—and this, it emerges, is frequently the case. Charles McLure, one of the architects of Treasury I, put it this way:

If … the financing of state and local public services reflected more accurately the benefit of such services, the case for reducing tax competition via federal subsidies would be weak and perhaps vanish. Indeed, in a world of user charges and benefit taxes the existence of such subsidies would worsen the allocation of resources, rather than improving it, by reducing the cost of such services to state and local beneficiaries/taxpayers and causing over-production of the subsidized activity.[41]

Whereas the federal government engages in a broad array of cash transfers, social insurance, and social welfare spending, such expenditures are responsible for a modest portion of state, and particularly local, budgets. Social services comprise 11.3 percent of local budgets, and general expenditures—which would include many of the amenities which might benefit nonresidents—only account for 5.6 percent of local government budgets nationwide.[42] This suggests that, unlike federal taxes, state and especially local taxes function hew closer to the benefit principle, and that federal subsidization of these levels of government will tend to favor taxpaying residents, not free-riding nonresidents.[43]

A more generalized case of suboptimal state and local budgeting is that of “fiscal imbalance,” where state and local expenditures are assumed to be suboptimal across the board, thus justifying federal subsidies designed to encourage higher levels of spending across all inferior governmental units.[44] To the extent that this concern is valid, however, the state and local deduction is a blunt instrument poorly suited to the task, as it flows most generously to those states and localities with the highest innate revenue capacity. Better calibration is possible with almost any other form of aid to states and localities.

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “State and Local Government Finances” (2014) | |||

|

Expenditure |

State & Local |

State |

Local |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Education Services |

28.1% |

18.3% |

37.0% |

|

Social Services |

24.7% |

39.3% |

11.3% |

|

Insurance Trust Expenditure |

10.0% |

17.9% |

2.7% |

|

Public Safety |

7.2% |

4.6% |

9.6% |

|

Utilities |

6.7% |

1.7% |

11.3% |

|

Transportation |

5.9% |

6.5% |

5.4% |

|

Environment & Housing |

5.8% |

2.2% |

9.1% |

|

General Expenditures |

4.4% |

3.1% |

5.6% |

|

Government Administration |

3.9% |

3.4% |

4.4% |

|

Interest on Debt |

3.3% |

2.9% |

3.6% |

A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis summarized the effect of the deduction by noting that it “may spur state and local governments to provide services that are neither federal in nature nor targeted toward areas of national concern” and thus “interfere with the sorting mechanism that otherwise helps keep local public services at levels appropriate to their value to local taxpayers.”[45] One of the virtues of federalism is the ability for state and local governments to experiment with different models of taxation and service provisions, with the recognition that what is appropriate or desirable for one population may be disfavored by another. Whatever balance communities might otherwise adopt, however, may be skewed by deductibility. As the CBO notes, “Because of the subsidy, too many of those services may be supplied, and state and local governments may be bigger as a result.”[46]

Additionally, the existence of the deduction can incentivize government provision of municipal services that might be provided more efficiently by the private sector, not because of some advantage or preference for government provision of the service, but because the cost, for instance, of municipal trash collection receives the benefit of the state and local tax deduction, whereas the economically equivalent private provision of waste management services would receive no such tax advantage.[47] From the start, local taxes remitted in exchange for local benefits (like license taxes) were not deductible.[48] In part because the deduction gives an advantage to general taxes over fees, any principle of excluding “consumption” argues against the deduction more broadly.

The Double TaxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. Argument

The coexistence of federal and state income taxes absent deductibility is sometimes characterized as a tax upon a tax, as federal taxes are paid on the share of income foregone to state (and potentially local) governments. Most taxes imposed by different levels of government are susceptible to some variation of this argument, but the crux of the case for deductibility is the taxpayer’s ability to pay. As noted previously, at times when the top marginal federal individual income tax rate exceeded 90 percent, it would have been possible for some income to be taxed at combined rates in excess of 100 percent in the absence of deductibility.

It is, of course, fairly implausible to conclude that rates would have stood as high in the absence of the deduction, or that earning a marginal dollar above some threshold would actually expose the taxpayer to more than a dollar’s worth of taxes. Even if such fears were warranted, however, they have little relevance under today’s rate schedule, or any rates which might emerge from a tax reform package which includes the repeal of the state and local tax deduction.

This argument for the deduction also depends on the extent that higher levels of state and local taxation represent, at least in part, a choice about the consumption of government services. If state and local tax rates are largely invariant to service provision or fund services not utilized by many taxpayers, then these state and local taxes may be seen as reducing capacity to pay federal taxes. If, however, these taxes correlate strongly with services provided—and such a correlation is far stronger at the state and local level than it is at the federal level—then arguments about double taxation are less salient,[49] particularly when variations in local government taxation can be explained in part by consumption that might otherwise have been supplied by the private sector.

In a federal system, moreover, individuals receive services from federal, state, and municipal governments. Each layer of government can be viewed as providing its own package of services, which one would expect to be “priced” separately. When two taxes levied by a single government, or similar types of governments (for instance, multiple states), fall disproportionately upon the same income or economic activity, this represents a clear case of double taxation. When different levels of governments levy taxes for discrete sets of services, the rationale for a deduction for taxes paid is far weaker.

A closely related argument holds that a large proportion of local government expenditures—schools, roads, police and fire protection, and the like—can be understood as investments in human and physical capital, and thus would be deductible as capital expenditures under an ideal tax code. Of course, not all local government spending can be reasonably construed as capital investment. States government budgets, moreover, tend to include far more welfare spending and transfers that clearly do not constitute capital expenditures.

The strength of this argument for local, if not for state, governments, turns at least in part on whether it is appropriate to consider a mandatory tax payment a capital expenditure even if the return to capital is accrued by other people or entities. When individuals and businesses purchase capital goods, they are—or at least they can designate—the intended beneficiary of any return on investment. When governments levy taxes, the payors have little control over either the investment or its beneficiaries.

Federal Revenue Implications

According to the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model, eliminating the state and local tax deduction would raise an additional $1.8 trillion in federal revenues over a ten-year window on a static basis, and $1.7 trillion on a dynamic basis which takes changes in economic activity into account.[50] The adverse economic impact is estimated at a modest 0.4 percent reduction in gross domestic product (GDP),[51] which would be more than counterbalanced by any offsetting rate reductions. The small impact on economic growth makes it an enticing offset for more growth-oriented revenue-reducing reforms elsewhere in the system.

Distributionally, the lower four quintiles of households would see their after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. decrease by 0 to 0.7 percent on a static basis under the deduction’s repeal. Households in the highest quintile would experience a tax increase of 2.2 percent on their income.[52] Dynamic effects, which take into account changes in behavior associated with taxes, are slightly larger.

|

Income Quintile |

Static % Change in After-Tax Income |

Dynamic % Change in After-Tax Income |

|---|---|---|

|

0% to 20% |

0.0% |

-0.3% |

|

20% to 40% |

-0.1% |

-0.4% |

|

40% to 60% |

-0.3% |

-0.6% |

|

60% to 80% |

-0.7% |

-1.0% |

|

80% to 100% |

-2.2% |

-2.5% |

| Source: Tax Foundation, Options for Reforming America’s Tax Code. | ||

Conclusion

Increasingly a costly anachronism which favors high-income earners in wealthy states, the state and local tax deduction has long outlived its usefulness. As such, it is an attractive “pay-for” to provide a revenue offset to rate reductions or other reforms. The House Republican tax plan would repeal the provision outright, while the campaign proposals of President Donald Trump promote caps on itemized deductions, which would limit the value of the deduction.

Whether as part of a plan emerging from one of these proposals, or as part of a tax reform plan still on the horizon, the end of the deduction for state and local taxes paid offers a rare convergence of the goals of both the left and the right, offering the opportunity to roll back a regressive element of the tax code to offset the cost of pro-growth reform. Forty years after the first rumblings of discontent in the Treasury’s Blueprints for Basic Tax Reform, the repeal of the state and local tax deduction may be an idea whose time has come.

[1] Sarah F. Liebschutz & Irene Lurie, “The Deductibility of State and Local Taxes,” Publius 16, no. 3 (Summer 1986): 51.

[2] Jeffrey Birnbaum & Alan Murray, Showdown at Gucci Gulch: Lawmakers, Lobbyists, and the Unlikely Triumph of Tax Reform (New York: Random House, Inc., 1987), 48.

[3] Internal Revenue Service, “Topic 503 – Deductible Taxes,” https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc503.html.

[4] Yuri Shandusky, “State and Local Tax Deductions,” Tax Notes (July 1, 2013): 87.

[5] Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income, Historical Table 2, 2014, https://www.irs.gov/uac/soi-tax-stats-historic-table-2.

[6] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Tax Expenditures [FY 2018],” Department of Tax Analysis, Sept. 28, 2016, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/Tax-Expenditures-FY2018.pdf, 34. For purposes of rankings, we combine defined contribution and defined benefit employer pension plans into one larger expenditure, as we do with the components of state and local tax deductibility. With all expenditures considered separately, deductibility of state and local taxes other than those on owner-occupied homes currently ranks seventh, while deductibility for taxes paid on owner-occupied homes ranks twelfth.

[7] Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income.

[8] Kyle Pomerleau, “The Pease Limitation on Itemized Deductions Is Really a SurtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. ,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Oct. 16, 2014, http://taxfoundation.org/blog/pease-limitation-itemized-deductions-really-surtax.

[9] See generally, Kyle Pomerleau, “Details and Analysis of the 2016 House Republican Tax Reform Plan,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 516, July 5, 2016, http://taxfoundation.org/article/details-and-analysis-2016-house-republican-tax-reform-plan.

[10] Liebschutz & Lurie, 52.

[11] Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 31, in The Federalist Papers, ed. Clinton Rossiter (New York: New American Library, 1961), 189-192.

[12] See generally, Tax Foundation, “U.S. Federal Individual Income Tax Rates History, 1862-2013 (Nominal and InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. -Adjusted Brackets),” Oct. 17, 2013, http://taxfoundation.org/article/us-federal-individual-income-tax-rates-history-1913-2013-nominal-and-inflation-adjusted-brackets.

[13] Liebschutz & Lurie, 54.

[14] Department of the Treasury, Blueprints for Basic Tax Reform, Jan. 17, 1977, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/Report-Blueprints-1977.pdf, 93.

[15] Louis Kaplow, “Fiscal Federalism and the Deductibility of State and Local Taxes in a Federal Income Tax,” 82 Va. L. Rev. 413 (1996): 416.

[16] Birnbaum & Murray, 48.

[17] Id., 109-113.

[18] Congressional Budget Office, “The Deductibility of State and Local Taxes,” Feb. 2008, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/110th-congress-2007-2008/reports/02-20-state_local_tax.pdf, 4.

[19] Gilbert Metcalf, “Assessing the Federal Deduction for State and Local Tax Payments,” National Tax Journal 64, vol. 2 (June 2011): 565.

[20] Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income.

[21] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2015-2019,” Dec. 7, 2015, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4857, 45-46.

[22] Liebschutz & Lurie, 55.

[23] Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income.

[24] Metcalf, 575.

[25] Edward M. Gramlich, “The Deductibility of State and Local Taxes,” National Tax Journal 38, no. 4 (Dec. 1985): 448.

[26] Id., 463.

[27] Bruce Bartlett, “The Case for Eliminating Deductibility of State and Local Taxes,” Tax Notes (Sept. 2, 1985): 1122

[28] Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income.

[29] Frank Sammartino & Kim Rueben, “Revisiting the State and Local Tax Deduction,” Tax Policy Center, March 31, 2016, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/2000693-Revisiting-the-State-and-Local-Tax-Deduction.pdf, 1.

[30] Shandunsky, 87.

[31] Sammartino & Rueben, 7-8.

[32] Bartlett, 1123.

[33] Liebschutz & Lurie, 64.

[34] Metcalf, 568.

[35] Gramlich, 462-463.

[36] Id., 568. See, e.g., Feldstein and Metcalf (1987), Holtz-Eakin & Rosen (1986), Metcalf (1993), and Gade & Adkins (1990).

[37] Congressional Budget Office, “The Deductibility of State and Local Taxes,” 7.

[38] Helen Ladd, as cited in Bartlett, 1123.

[39] Id.

[40] Charles McLure, “Tax Competition: Is What’s Good for the Private Goose Also Good for the Public Gander?” National Tax Journal 39, no. 3 (Sept. 1986): 344.

[41] Id., 342.

[42] U.S. Census Bureau, “State and Local Government Finances,” 2014, https://www.census.gov/govs/local/.

[43] Bartlett, 1124

[44] Liebschutz & Lurie, 55.

[45] Congressional Budget Office, “The Deductibility of State and Local Taxes,” 7.

[46] Id.

[47] Jeremy Horpedahl and Harrison Searles, “The Deduction of State and Local Taxes from Federal Income Taxes,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 3.

[48] Sammartino & Rueben, 7.

[49] Congressional Budget Office, “Option 6: Eliminate the Deduction for State and Local Taxes,” Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2014 to 2023, Nov. 13, 2013, https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/2013/44799.

[50] Tax Foundation, Options for Reforming America’s Tax Code, http://taxfoundation.orghttps://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/TF_Options_for_Reforming_Americas_Tax_Code.pdf, 49.

[51] Id.

[52] Id.

Share